We’re Your Community for Suicide-Specific Care.

The people behind CAMS-care are suicidology experts committed to enhancing our systems of care and saving lives. We’re here to support you navigate suicide prevention and treatment with empathy, compassion, and evidence-based solutions.

Leadership

Colleen Kelly, Esq.

Founder & Legal Counsel

Andrew Evans

President & COO

Kevin Crowley, Ph.D.

Training Solutions – U.S.

Mariam Gregorian, Ph.D.

Training Solutions – U.S.

Anne Wiemers

Director of Operations

Tanisha Jarvis

Diversity Consultant

Ashleigh Edelman

Website Marketing Director

Tracy Kelly

Director of Marketing Strategy

Heidi Hamamoto

Operations Systems Manager

Rachel Bryer

Billing & Fulfillment Manager

Catherine Gorzynski

Customer Success Manager

Meghan Zavadil

Operations Specialist

Our Consultants

Jennifer Crumlish, Ph.D., ABPP

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist and Assistant Director, The Catholic University of America Suicide Prevention Laboratory, Washington, DC.

Mariam Gregorian, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist, Private Practice, Washington, D.C.

Kevin Crowley, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist, Capital Institute for Cognitive Therapy, Washington, D.C.

Melinda Moore, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist and Associate Professor of Psychology, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, KY.

Natalie Burns, LMSW, MA

Consultant

Licensed Master Social Worker, Catholic University

Senior Clinical Social Worker, University of Michigan Medicine

Amy Brausch, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist and Associate Professor of Psychological Sciences, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY.

Raymond P. Tucker, Ph.D.

Consultant

Assistant Professor of Psychology, Louisiana State University (LSU)

Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (LSUHSC)/Our Lady of the Lake (OLOL)

Kurt D. Michael, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychologist, Aeschleman Distinguished Professor, Appalachian State University (Retired), Senior Clinical Director, Jed Foundation, High School Programs

Samantha Chalker, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist, San Diego, CA

Clinical Psychologist, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, Research Scientist, VA San Diego Healthcare System

Blaire Ehret, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist, Assistant Program Manager and Clinical Supervisor, Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Center, VA San Diego Healthcare System, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, Board Member, Survivors of Suicide Loss, San Diego

John Drozd, Ph.D., ABMP

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist, Board Certified Medical Psychologist, Academy of Medical Psychology

Josephine Au, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical and Research Psychologist

Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School

Asher Siegelman, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist, PsychCare of Maryland

Beit Shemesh, Israel

CAMS-care Israel

Emma Cardeli, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical and Research Psychologist

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School

Zaffer Iqbal, Ph.D., DClinPsy, AFBPsS

Consultant

Head of Psychological Services and Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Navigo CiC (NHS) UK; Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Hull, UK

Paulina Arenas-Landgrave, Ph.D.

Consultant

Clinical Psychologist and Full Professor of Psychology, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City.

Are you interested in becoming a CAMS-care Consultant?

We’d love to connect with you!

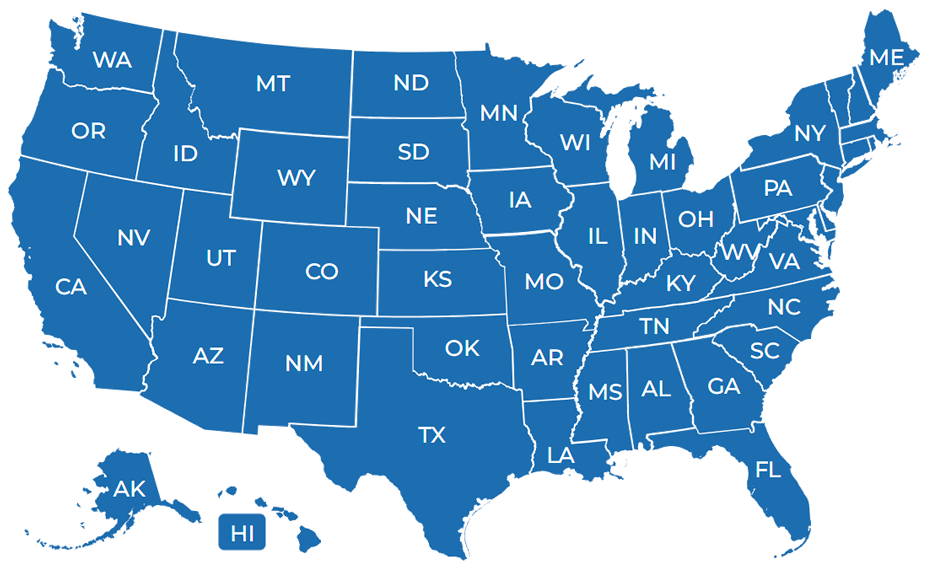

Clinician Locator

Find a CAMS-Trained™ clinician who can help you, or your loved one, struggling with suicidal thoughts and feelings.