As discussed elsewhere, there are over 80 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of treatments where suicide-related outcomes are the primary focus [20,62]. Within clinical science, RCTs are the gold standard of what has proven effective in a causal manner because of their reliance on experimental designs and a-priori hypothesis testing. RCTs that have replicated results, particularly when results have been replicated by independent investigators rise to the top of the list when we consider empirically validated interventions. There are a number of interventions that have shown promise in a single RCT, for example, the Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (ASSIP) and Mentalization-Based Therapy [63,64]. However, we will focus on treatments that have been replicated and have independent RCT support. These include four distinct treatments/interventions that have been shown to effectively target suicidality.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy Treatment

The most notable and heavily researched treatment that has been shown to reduce suicidal behaviors regardless of the intent to die, is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) [65,66]. DBT has four main components: individual therapy, skills training, phone coaching, and a consultation team. DBT’s main goal is to teach the patient skills to regulate emotions and improve relationships with others (suicidality is always targeted at the forefront of care). Skills are taught through validation and acceptance with a genuine focus on behavioral change. DBT was one of the first evidence-based treatments shown to be effective in decreasing repetitive self-harm behaviors and suicide attempts. More recent results have demonstrated DBT’s continued impact on decreasing suicidal behaviors among high risk individuals such as those with borderline personality disorder [67], and decreasing suicide ideation [68] and self-harm [69] among adolescents. However, while DBT has shown impressive results in managing suicidal behaviors [70], it is not solely devoted to treating suicidality, and replicated results for reliably decreasing suicidal ideation are not consistent across all DBT RCTs.

Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention

Another effective treatment that targets the “suicidal mode” is Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CT-SP) [71]. CT-SP treats the clinical characteristics of suicidal behaviors [72] by using various cognitive therapy techniques, which have proven successful for treating an extensive array of psychiatric disorders [73]. In a well-powered RCT (with a deliberately longer follow-up period than previous RCTs—18 months), Brown and colleagues [71] found that patients in CT-SP treatment were 50% less likely to attempt suicide compared to those in the usual care treatment group. The researchers also found significant reductions in levels of depression and hopelessness in the CT-SP treatment group compared to the control. This study showed high internal validity; replication of the data in a real world setting (e.g., a community-based outpatient setting) with varied samples (e.g., those who have not attempted suicide, but with severe ideation) is a pending next step for the researchers of CT-SP [71].

Brief Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Suicidal Patients

Brief Cognitive Behavior Therapy (BCBT) was used in one well-powered RCT with suicidal, active duty U. S. Army Soldiers and was shown to be effective for reducing suicide attempts [29]. As its name indicates, this modality is brief (i.e., 12 sessions) to accommodate short-term treatment environments. This variation of CBT suicide-focused care emphasizes: common effective treatment elements, developing skills (e.g., emotion regulation, mindfulness), a focus on the suicidal mode, and the development of self-management. Rudd and colleagues followed soldiers for 24 months [29] and found that compared to treatment as usual, those in the brief CBT group were 60% less likely to attempt suicide.

The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality

Jobes describes the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) as a distinctive therapeutic framework that targets suicidality [32]. As a framework, not a new psychotherapy, the CAMS intervention does not require clinicians to give up their theoretical orientation or abandon reliable techniques. Indeed, CAMS is a “non-denominational” approach where potentially any treatment can be used within the framework [31]. In RCTs comparing CAMS to usual care control conditions there is strong evidence that CAMS significantly reduces suicidal ideation [74–76] and overall psychiatric distress [74,76]; it also increases hope and retention to care [74]. In on RCT comparing DBT to CAMS, CAMS did as well as DBT in reducing suicidal attempts and self-harm behaviors [77]. Beyond the initial four published RCTs, five additional CAMS RCTs are in various stages of completion and will add to this growing body of literature.

Stepped Models of Care

Finally, because this journal broadly addresses public health issues, it is important to wrap up our discussion by focusing on some major considerations that impact clinical care before we discuss two different conceptual models for thinking about suicide-specific clinical care that might optimize treatment outcomes and thereby save more lives.

The Stigma of Mental Health Care and Suicidality

In the investigation of the challenges posed by suicidal risk, one of the most striking issues is that the majority of suicidal people simply do not seek mental health treatment. Indeed, in their review of the literature Luoma et al. found that only 19% sought mental health care in the month prior to their death [78], while 32% sought mental health care in the year prior to their suicide. Using National Violent Death Reporting System data, Niederkrotenthaler and colleagues [79] found that only 38.5% suicide decedents were engaged in mental health care within two months of their death.

Furthermore, a sample of 198 suicidal people noted that “using the mental health system” was their #4 coping strategy (preceded by “spirituality/religious practices,” “talking to someone and companionship,” and “positive thinking”) [41]. Frankly, many suicidal people do not want to seek professional treatment because of their negative attitudes towards mental health care [80]. As Allen and colleagues have noted [42], when suicidal people do seek professional care (e.g., ED-based care), they want something different than what they get (e.g., a more humanistic and person-centered clinical response).

Matching Different Treatments to Personalize Suicidal Treatment

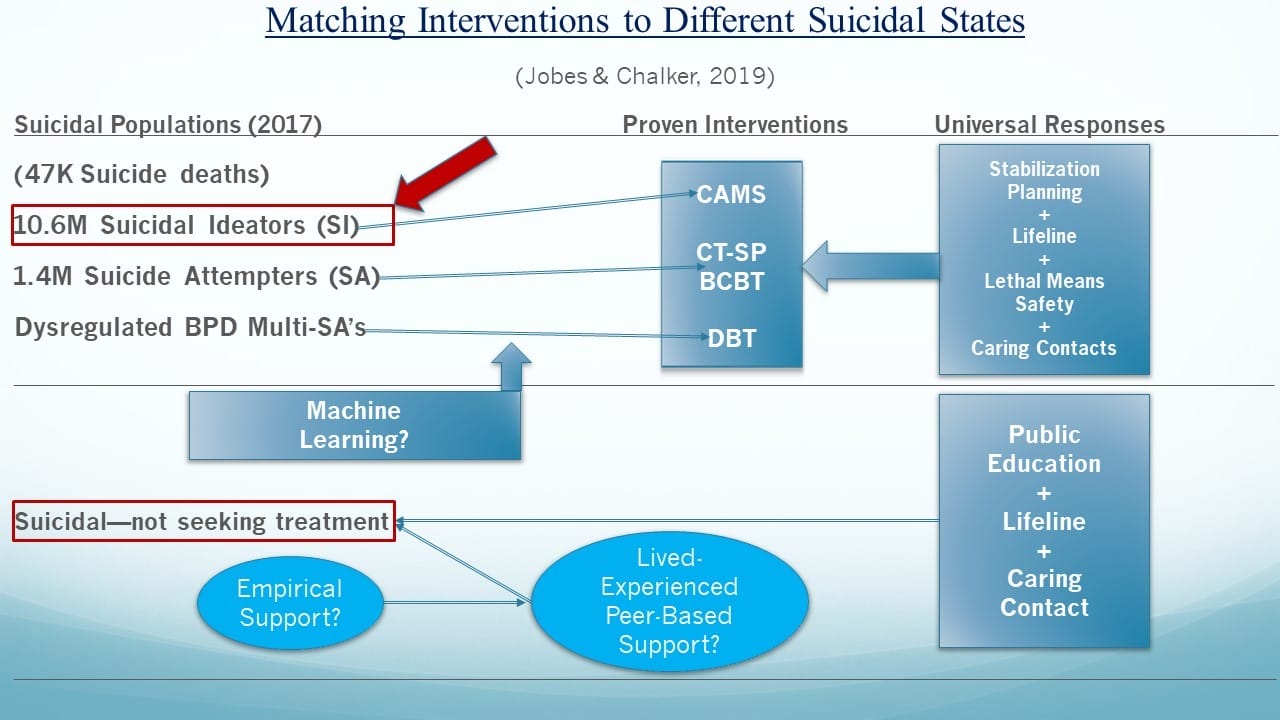

Despite the aforementioned concerns, we believe that the notion of prescriptive suicide-focused treatments is now increasingly possible. As shown in the lower half of Figure 1, the discussion begins with suicidal people who do not want to seek professional care. As we noted, this population make up the majority of the suicidal population. We can aspire to educate, provide access to the National Lifeline, and if they touch healthcare systems, perhaps we can endeavor to provide caring follow-up.

However, beyond these largely public health-oriented approaches, we do not know exactly how to reach this group. Perhaps the evolving lived-experience perspective and peer-support movement can provide a more accessible and less stigmatizing approach for this population.

Figure 1. Different suicidal states include suicidal ideators (SI), suicide attempters (SAs), and multiple SAs. For those that seek mental health care: (SI) may be best matched to the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS), SAs may be best matched to Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CT-SP) or Brief Cognitive Behavior Therapy (BCBT), and dysregulated individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) with a multiple SA history may be best matched to Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). Those that are suicidal but do not seek mental health treatment may be best matched to those with live-experienced and peer-based supports. Lifeline = the United States national suicide prevention lifeline phone number: 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Considering the upper half of the Figure 1, for those suicidal people seeking mental health care, in an ideal world, machine-learning algorithms could be used to optimally route patients to proven treatments that are best suited to care for different suicidal states—a version of empirically-based prescriptive suicide-focused treatments. It should be noted that similar components (e.g., stabilization planning, lethal means safety, etc.) tend to be integral in each of these effective treatments. As a final note, while focusing on suicide attempts and deaths is important and necessary, we also need to bring more attention to the massive population of seriously suicidal ideators, who represent the figurative iceberg under the water of the suicide prevention challenge, if we want to reduce suicidal attempts and completions [3].

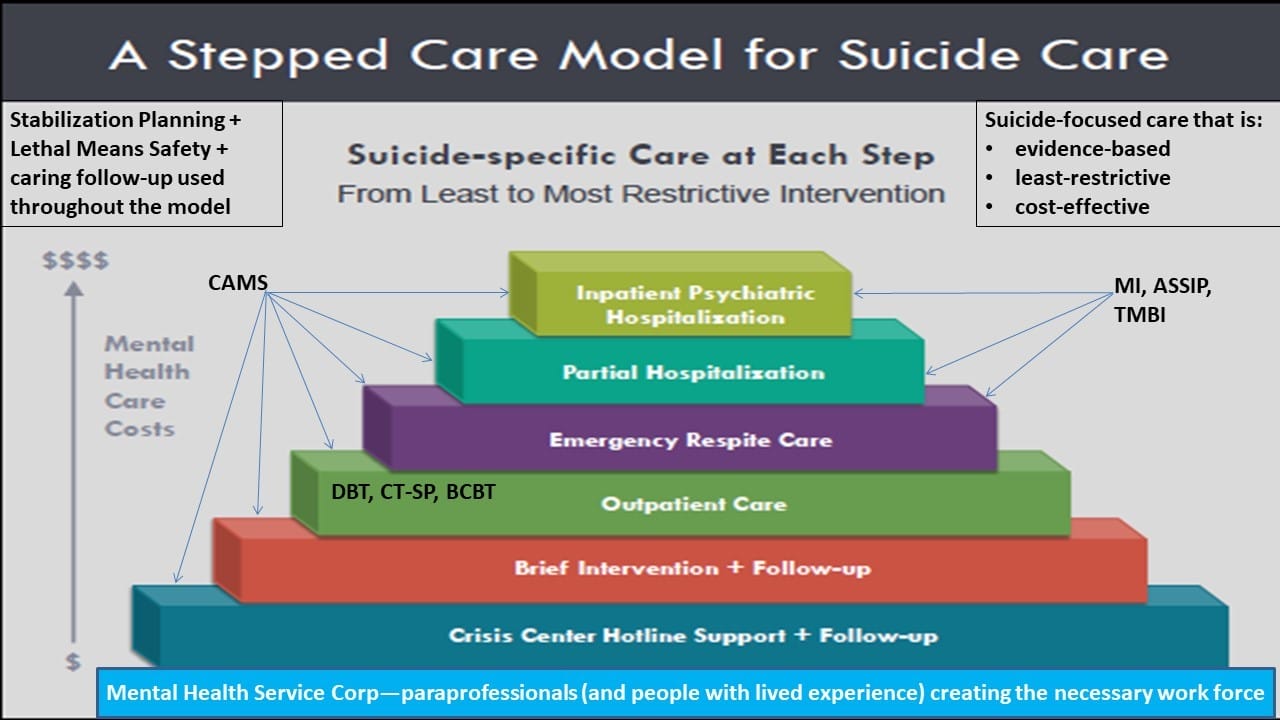

From an even larger perspective, Figure 2 (adapted from an earlier figure that appears in [81]) depicts a “stepped care” model for suicide care. The healthcare costs, represented on the y-axis, are probably the single biggest force shaping healthcare practices in the real world. To this end, the top of the pyramid notes the most expensive systems-level interventions (i.e., inpatient psychiatric hospitalization) down to the least expensive interventions nearer the bottom of the pyramid. Moreover, the bottom layer reflects the need to grow a massive paraprofessional community of caring people who are trained to work with people at risk. Jobes has therefore called for the development of a “National Mental Health Service Corps” (similar to the United States Peace Corps founded in the 1960s) that could create a large community of volunteers and (or) provide caring individuals who could serve in a range of capacities, such as screening and peer-based support with proper training and supervision [82]. There will never be enough clinical providers to meet the needs of 10.6 million adults with serious suicidal thoughts (in the United States example). Indeed, such personnel could provide much needed care on the National Lifeline, which is currently facing significant capacity issues.

Figure 2. The y-axis is mental health care costs; the steps of the pyramid correspond from the bottom to the top with the least restrictive intervention the most restrictive intervention. ASSIP = Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program; BCBT = Brief Cognitive Behavior Therapy; CAMS = Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality; CT-SP = Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention; DBT = Dialectical Behavior Therapy; MI = Motivational Interviewing; PACT = Post Admission Cognitive Therapy; TMBI = Teachable Moment Brief Intervention.

As we move up the levels of systems within the pyramid, the use of different evidence-based treatments described in this article can be layered in each level of clinical care. Ultimately this stepped care model provides a way of thinking broadly to providing cost-effective, least-restrictive, evidence-based care for those at risk for suicide. If we truly aim to make a lifesaving difference, public and mental policy shaped by this kind of approach might make a meaningful difference by reducing suicides and suicide-related suffering in all its forms.

Summary and Conclusions

We have argued in this article that to move the field of mental health forward in terms of suicidal risk, we must move away from a “one-size-fits-all” approach to working with suicidal people. Rather, an approach that matches different evidence-based suicide-focused treatments (i.e., DBT, CT-SP, BCBT, and CAMS) to different suicidal states is clearly needed. We also need thoughtful conceptual models and progressive evidence-based policies (e.g., Zero Suicide) to optimally engage those suicidal people who do not seek care. Finally, an array of professional and paraprofessional approaches (e.g., including the support of those with lived experience) and various services are needed to better support those people who battle with suicidal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Conflicts of Interest: David Jobes has conflicts to disclose related to grant funding from the National Institute of Mental Health and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; he receives book royalties from the American Psychological Association Press and Guilford Press; and he is the founder of CAMS-care, LLC (a professional training and consultation company). Samantha Chalker has no conflicts to disclose.

- Jobes, D.A. Clinical assessment and treatment of suicidal risk: A critique of contemporary care and CAMS as a possible remedy. Pract. Innov. 2017, 2, 207–220. [CrossRef]

- Jobes, D.A. One size does not fit all: Matching empirically proven interventions to different suicidal states. In Proceedings of the American Association of Suicidology, Denver, CO, USA, 24–27 April 2019.

- Dweck, C. Mindset: Changing the Way You Think to Fulfil Your Potential; Hachette UK: London, UK, 2012.

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K. Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2012, 19, 256–264. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K.; Brenner, L.A.; Galfalvy, H.C.; Currier, G.W.; Knox, K.L.; Chaudhury, S.R.; Bush, A.L.; Green, K.L. Comparison of the Safety Planning Intervention with Follow-up vs. Usual Care of Suicidal Patients Treated in the Emergency Department. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 894–900.

- Rudd, M.D.; Joiner, T.E.; Rajab, M.H. Treating Suicidal Behavior: An Effective, Time-Limited Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004.

- Bryan, C.J.; Corso, K.A.; Neal-Walden, T.A.; Rudd, M.D. Managing suicide risk in primary care: Practice recommendations for behavioral health consultants. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 148. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Mintz, J.; Clemans, T.A.; Burch, T.S.; Leeson, B.; Williams, S.; Rudd, M.D. Effect of crisis response planning on patient mood and clinician decision making: A clinical trial with suicidal US soldiers. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 69, 108–111. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Mintz, J.; Clemans, T.A.; Leeson, B.; Burch, T.S.; Williams, S.R.; Maney, E.; Rudd, M.D. Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in US Army Soldiers: A randomized clinical trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 212, 64–72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, M.D.; Bryan, C.J.; Wertenberger, E.G.; Peterson, A.L.; Young-McCaughan, S.; Mintz, J.; Williams, S.R.; Arne, K.A.; Breitbach, J.; Delano, K.; et al. Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts in a military sample: Results of a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 441–449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, M.D.; Mandrusiak, M.; Joiner, T.E. The case against no-suicide contracts: The commitment to treatment statement as a practice alternative. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 243–251. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobes, D.A. Managing Suicidal Risk: A Collaborative Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Jobes, D.A. Managing Suicidal Risk: Second Edition: A Collaborative Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Motto, J.A.; Bostrom, A.G. A randomized controlled trial of post crisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 828–833. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reger, M.A.; Luxton, D.D.; Tucker, R.P.; Comtois, K.A.; Keen, A.D.; Landes, S.J.; Matarazzo, B.B.; Thompson, C. Implementation methods for the caring contacts suicide prevention intervention. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pr. 2017, 48, 369–377. [CrossRef]

- Luxton, D.D.; June, J.D.; Comtois, K.A. Can post discharge follow-up contacts prevent suicide and suicidal behavior? Crisis 2012, 46–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comtois, K.A.; Kerbrat, A.H.; DeCou, C.R.; Atkins, D.C.; Majeres, J.J.; Baker, J.C.; Ries, R.K. Effect of augmenting standard care for military personnel with brief caring text messages for suicide prevention: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 474–483.[PubMed]

- Carey, B. Expert on mental illness reveals her own struggle. New York Times. Available online: https://www.sadag.org/images/pdf/expert%20own%20fight.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Hogan, M.F.; Grumet, J.G. Suicide prevention: An emerging priority for health care. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1084–1090. [CrossRef]

- Dimeff, L.A.; Jobes, D.A.; Chalker, S.A.; Piehl, B.M.; Duvivier, L.L.; Lok, B.C.; Zalake, M.S.; Chung, J.; Koerner, K. A novel engagement of suicidality in the emergency department: Virtual Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bruffaerts, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Hwang, I.; Chiu, W.T.; Sampson, N.; Kessler, R.C.; Alonso, J.; Borges, G.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; et al. Treatment of suicidal people around the world. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 64–70. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.J.; Haugland, G.; Ashenden, P.; Knight, E.; Brown, I. Coping with thoughts of suicide: Techniques used by consumers of mental health services. Psychiatr. Serv. 2009, 60, 1214–1221. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.H.; Carpenter, D.; Sheets, J.L.; Miccio, S.; Ross, R. What do consumers say they want and need during a psychiatric emergency? J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2003, 9, 39–58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre, R.T.P.; Slater, H.M. Suicide postvention as suicide prevention: Improvement and expansion in the United States. Death Stud. 2010, 34, 529–540. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begley, M.; Quayle, E. The lived experience of adults bereaved by suicide: A phenomenological study. Crisis 2007, 28, 26–34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Force, S.A. The Way Forward: Pathways to Hope, Recovery, and Wellness with Insights from Lived Experience; National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Crisis Now. 2019. Available online: https://crisisnow.com (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Live Through This. 2019. Available online: https://livethroughthis.org (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Now Matters Now. 2019. Available online: https://www.nowmattersnow.org (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- MacLean, S.; MacKie, C.; Hatcher, S. Involving people with lived experience in research on suicide prevention. CMAJ 2018, 190, S13–S14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Alert: Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings. Jt. Comm. 2016, 56, 1–7.

- Brodsky, B.S.; Spruch-Feiner, A.; Stanley, B. The zero suicide model: Applying evidence-based suicide prevention practices to clinical care. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zero Suicide. 2019. Available online: https://zerosuicide.sprc.org (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- National Suicide Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: Transforming Health Systems Initiative Work Group. Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe; Education Development Center, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Durkheim, E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology, 1987; Spaulding, J.A.; Simpson, G., Translators; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1951.

- Conrad, A.K.; Jacoby, A.M.; Jobes, D.A.; Lineberry, T.W.; Shea, C.E.; Arnold Ewing, T.D.; Schmid, P.J.; Ellenbecker, S.M.; Lee, J.L.; Fritsche, K.; et al. A psychometric investigation of the suicide status form II with a psychiatric inpatient sample. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2009, 39, 307–320.[PubMed]

- Kleiman, E.M.; Turner, B.J.; Fedor, S.; Beale, E.E.; Huffman, J.C.; Nock, M.K. Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 726. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, J.S. Typologies of Suicidal Patients Based on Suicide Status Form Data. Ph.D. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Stanley, I.H.; Rufino, K.A.; Rogers, M.L.; Ellis, T.E.; Joiner, T.E. Acute suicidal affective disturbance (ASAD): A confirmatory factor analysis with 1442 psychiatric inpatients. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 80, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Galynker, I.; Yaseen, Z.S.; Cohen, A.; Benhamou, O.; Hawes, M.; Briggs, J. Prediction of suicidal behavior in high risk psychiatric patients using an assessment of acute suicidal state: The suicide crisis inventory. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 147–158. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobes, D.A. The challenge and the promise of clinical suicidology. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1995, 25, 437–449. [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Chalker, S.A.; Luedtke, A.R.; Sadikova, E.; Jobes, D.A. A preliminary precision treatment rule for collaborative assessment and management of suicidality relative to enhanced care-as-usual in prompting rapid remission of suicide ideation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bridge, J.A.; Iyengar, S.; Salary, C.B.; Barbe, R.P.; Birmaher, B.; Pincus, H.A.; Ren, L.; Brent, D.A. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2007, 297, 1683–1696. [PubMed]

- Gysin-Maillart, A.; Schwab, S.; Soravia, L.; Megert, M.; Michel, K. A novel brief therapy for patients who attempt suicide: A 24-months follow-up randomized controlled study of the attempted suicide short intervention program (ASSIP). PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001968. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, A.; Fonagy, P. 8-year follow-up of patients treated for borderline personality disorder: Mentalization-based treatment versus treatment as usual. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 631–638. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993.

- Linehan, M.M.; Comtois, K.A.; Murray, A.M.; Brown, M.Z.; Gallop, R.J.; Heard, H.L.; Korslund, K.E.; Tutek, D.A.; Reynolds, S.K.; Lindenboim, N. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 757–766.

- Linehan, M.M.; Korslund, K.E.; Harned, M.S.; Gallop, R.J.; Lungu, A.; Neacsiu, A.D.; McDavid, J.; Comtois, K.A.; Murray-Gregory, A.M. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: A randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 475–482.

- Goldstein, T.R.; Fersch-Podrat, R.K.; Rivera, M.; Axelson, D.A.; Merranko, J.; Yu, H.; Brent, D.A.; Birmaher, B. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: Results from a pilot randomized trial. J. Child Adole. Psychopharm. 2015, 25, 140–149. [CrossRef]

- Mehlum, L.; Ramberg, M.; Tørmoen, A.J.; Haga, E.; Diep, L.M.; Stanley, B.H.; Miller, A.L.; Sund, A.M.; Grøholt, B. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with enhanced usual care for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: Outcomes over a one-year follow-up. J. Am. Acad. Child Adole. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 295–300. [CrossRef]

- DeCou, C.R.; Comtois, K.A.; Landes, S.J. Dialectical behavior therapy is effective for the treatment of suicidal behavior: A meta-analysis. Behav. Ther. 2019, 50, 60–72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.K.; Have, T.T.; Henriques, G.R.; Xie, S.X.; Hollander, J.E.; Beck, A.T. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005, 294, 563–570.[PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Kovacs, M.; Weissman, A. Hopelessness and suicidal behavior: An overview. JAMA 1975, 234, 1146–1149.[PubMed]

- Beck, A.T. The current state of cognitive therapy: A 40-year retrospective. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 953. [PubMed]

- Comtois, K.A.; Jobes, D.A.; O’Connor, S.; Atkins, D.C.; Janis, K.; Chessen, C.; Landes, S.J.; Holen, A.; Yuodelis-Flores, C. Collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS): Feasibility trial for next-day appointment services. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 963–972. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobes, D.A.; Comtois, K.A.; Gutierrez, P.M.; Brenner, L.A.; Huh, D.; Chalker, S.A.; Ruhe, G.; Kerbrat, A.H.; Atkins, D.C.; Jennings, K.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of the collaborative assessment and management of suicidality versus enhanced care as usual with suicidal soldiers. Psychiatry 2017, 80, 339–356. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryberg, W.; Zahl, P.H.; Diep, L.M.; Landrø, N.I.; Fosse, R. Managing suicidality within specialized care: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 249, 112–120. [CrossRef]

- Andreasson, K.; Krogh, J.; Wenneberg, C.; Jessen, H.K.L.; Krakauer, K.; Gluud, C.; Thomsen, R.R.; Randers, L.; Nordentoft, M. Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy versus collaborative assessment and management of suicidality treatment for reduction of self-harm in adults with borderline personality traits and disorder: A randomized observer-blinded clinical trial. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 520–530. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, J.B.; Martin, C.E.; Pearson, J.L. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 909–916. [CrossRef]

- Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Logan, J.E.; Karch, D.L.; Crosby, A. Characteristics of US suicide decedents in 2005–2010 who had received mental health treatment. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 387–390. [CrossRef]

- Pitman, A.; Osborn, D.P.J. Cross-cultural attitudes to help-seeking among individuals who are suicidal: New perspective for policymakers. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 8–10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobes, D.A.; Gregorian, M.J.; Colborn, V.A. A stepped care approach to clinical suicide prevention. Psychol. Serv. 2018, 15, 243. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobes, D.A.; Kelly, C.A. Growing up in AAS. Presented at the American Association of Suicidology, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 21 April 2017.