Full article originally published September 26, 2019 in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Key Developments in Suicide Prevention May Be Changing Mindsets

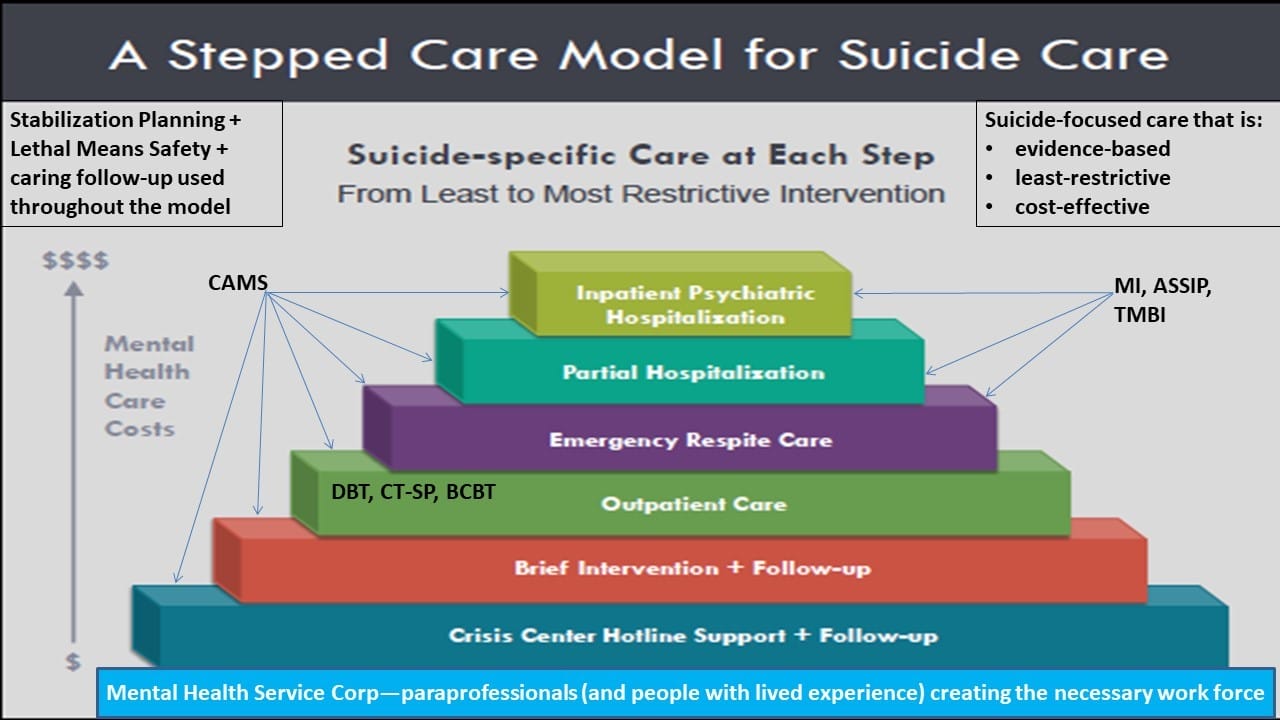

There are various contemporary developments that may help workers in the field to move from a fixed mindset about hospitalization and medications for all suicidal individuals to a growth mindset, which is supported by the extant RCT evidence-base and enhanced and evidence-based clinical practices, which can be further supported by progressive mental health policy.

Suicide Intervention Strategies & Stabilization Planning

Perhaps one of the most important developments over the past 20 years in clinical suicidology has been the development and use of different versions of suicide-focused interventions that focus on stabilization planning for prospective acute suicidal crises. In marked contrast to the coercive and unfortunate use of “No-Harm Contracts” or “No-Suicide Contracts,” various stabilization planning interventions for suicidal outpatients are intuitively more compelling and have proven effective in clinical trial research. The best known of these interventions is the Safety Plan Intervention (SPI) developed by Drs. Stanley and Brown [23]. Widely adopted in the American Veterans Affairs and the U.S. Department of Defense healthcare systems, the SPI has also been adopted in the public and private sectors as an alternative to coercive contracts that focus on what a patient promises not to do (i.e., kill themselves) versus planning for what they will do within a suicidal, dark moment of crisis. The Safety Plan guides the patient through the steps of identifying triggers, self-coping techniques, distraction by others, reaching out for supportive help, reaching out to professional help, and securing lethal means. Many have clinically embraced the Safety Plan Intervention early on as an intuitively better option to coercive no-suicide contracts (despite the absence of empirical support for so doing). Relatively recently however, the superiority of the SPI over no-harm contracting for reducing suicide attempt behaviors was clearly demonstrated [24] in a large cohort-comparison study of suicidal U.S. military veterans, and additional randomized controlled trial data are now being conducted.

A conceptual “cousin” of the SPI is the “Crisis Response Plan” (CRP), which was first developed by Rudd, Joiner, and Rajab [25] and further elaborated and rigorously studied by Bryan and colleagues [26–30]. The CRP has the patient note on an index card, in their own written words, various triggers, coping strategies, resources, and oftentimes their reasons for living. Bryan and colleagues [28] performed a convincing RCT comparing the CRP to no-harm contracts and showed a significant effect on both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, reducing the latter by 76% at the six-month follow-up assessment.

Another variation on this theme is the CAMS Stabilization Plan, which is developed in the initial session of the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) [31,32]. Within this therapeutic framework, the CSP emphasizes securing lethal means, which is followed by a list of coping strategies, resources for outreach, ways for decreasing isolation, and potential barriers to attending CAMS-guided clinical care. The CSP has not been independently studied outside of its use within CAMS, but it is a crucial tool that is routinely used within this evidence-based suicide-focused clinical treatment.

Caring Letters for Suicide Prevention

A rather stunning research development occurred when psychiatrist Jerome Motto had the idea of sending a “caring letter” to post-discharged psychiatric patients who refused to seek further mental health treatment. In their now famous RCT, Motto and Bostrom [33] found that sending a simple letter expressing concern and care every four months to patients post-discharge over five years caused a reduction in suicides, when compared to patients who did not receive caring letters. This elegantly simple study has been a transformative discovery for the field.

Motto’s seminal work has led to various replications using different forms of “caring contacts” that have involved different versions of the original Motto idea of using letters. Indeed, this simple, inexpensive and scalable intervention has been investigated using postcards, letters, emails, and text messages [34]. While some data have been mixed, a larger review of published caring contact trials found it to be generally effective in reducing suicidal behaviors [35]. Nevertheless, these authors noted the need for more rigorous caring contact RCTs. To this end, a recent RCT [36] with suicidal military personnel using caring contacts via text messages was compared to treatment as usual. The investigators found that those receiving caring contacts via text message were less likely to have any suicidal ideation and fewer attempts from baseline to 12 months. However, the likelihood or severity of suicidal ideation and the number of suicide risk incidents (i.e., hospitalization or medical evacuation) were not significantly different between groups.

Lived Experience Perspective

It is hard to estimate the impact of people who have “lived experience” with suicidal thoughts, attempts, and encounters with conventional mental health care. Among the earliest pioneers in this area were American Terri Wise and Australian Keith Harris. Marsha Linehan is perhaps the most famous person to poignantly describe her extensive experiences when she was a highly suicidal teenager [37]. In any case, there can be no question that the lived experience movement has had a significant impact on suicide prevention policy making [38], emerging clinical practices, and research Lived Experience Peer-Support Movement (e.g., [39])

Effectiveness of Lived Experience Peer-Support

The World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey determined that across 21 nations, a majority of individuals thinking, planning, and attempting suicide do not receive clinical treatments [40]. The major barriers for suicidal individuals to seek mental health care include low perceived need, attitudes to treatment (e.g., the wish to handle it on one’s own), and practical concerns (e.g., financial concerns). Given these considerations, there is a recognition of the need for other possible ways for suicidal individuals to relieve their suffering beyond traditional primary or psychiatric care [40].

A survey on how suicidal individuals cope with their suicidal thoughts showed overwhelmingly that talking with someone who was not a mental health professional was the primary response. Only 12% of respondents included talking to someone in the mental health profession [41]. Given these data, Alexander and colleagues [41] have advocated for education and support for family and peers as another line of intervention for loved ones in crisis. A desire for increased peer support services as a way to improve care was also noted among consumers who experienced a psychiatric emergency [42]. This research highlighted the desire for peer support to improve emergency care in a variety of situations including during physical restraint, being referred to a post-discharge peer support group, and assistance in securing post-discharge services. Some mental health policy advocates are now promoting various peer-support services as part of a compelling alternative to our contemporary current clinical practices within emergency services (refer to: https://crisisnow.com/#core_elements).

Generally speaking, those with lived experience have personally had suicidal thoughts, feelings, and/or engaged in suicidal behavior(s). Importantly, people with lived experience are also willing to share their experiences with others as they advocate for better mental health care and encourage others with lived experience to participate in their efforts to reform care for suicidal risk [43,44]. The emergence of this perspective is underscored by multiple national and international organizations who have devoted web link resources to support people with lived experience (e.g., the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, Zero Suicide, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, National Alliance of Mental Illness, Centre for Suicide Prevention, American Association of Suicidology, and International Association for Suicide Prevention).

At the national policy level in the U.S., the Suicide Attempt Survivors Task Force of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention has published “The Way Forward: Pathways to Hope, Recovery, and Wellness with Insights from Lived Experience” [45]. This landmark report focuses on suicide prevention practices that are evidenced-based while also incorporating personal testimonies of those with lived experience.

Lived experience advocates are now being promoted in many diverse areas to assist in the prevention of suicide. For instance, those with lived experience have created web pages (e.g., NowMattersNow.org; LiveThroughThis.org; CrisisNow.org) to document their experiences and also provide help to those seeking alternative treatments [46–48]. Help that is provided on these websites includes video testimonies and skills (e.g., dialectical behavior therapy skills). Moreover, lived experience participants have been included in randomized controlled trials to provide added support to more traditional “face-to-face” talk therapy. One study that examined men who presented to the emergency department for self-harm demonstrated that research studies can readily include individuals with lived experience [49]. A community can be formed around such a research project to provide long-lasting support within patient-centered research to offer an innovative way to reach more high-risk individuals [49].

Suicide Policy Developments

Over the past twenty years in the United States, there have been some notable suicide-specific policies that have significantly changed suicide-related clinical practices. By their very nature, these policies are designed to shift practitioners from a status quo approach to handling suicidal risk to utilizing alternative practices that are largely driven by empirical data.

Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alerts

The Joint Commission (TJC) accredits well over 21,000 healthcare settings across the United States. Because suicide-related fatal outcomes have been among the leading “sentinel events” (i.e., failures in care resulting in adverse outcomes), TJC has issued various Sentinel Event Alerts to notify accredited institutions that certain practices must change and be observed in accreditation site visits or possible sanctions may ensue. To the surprise of some within the healthcare industry, TJC issued a Sentinel Event Alert entitled “Detecting and Treating Suicide Ideation in all Settings” [50]. While the particular alert has been re-framed as “aspirational” (versus a required expectation), their intent is plain: take suicide seriously, identify the risk, and treat it.

Zero Suicide Initiative

Inspired by the work of the Clinical Care Task Force of the National Action Alliance, the “Zero Suicide” policy initiative has been game changing in terms of an A-Z approach to raising the clinical standard of care across systems of care by developing the following: leadership, training, assessment, identification (assessment), engagement, treatment, transition, and improvement [51,52]. While there has been some controversy connected to the name, there can be no arguing the abject success. Zero Suicide policies are embraced across the United States and now around the world. It is fair to say there is no policy initiative in the history of suicide prevention that has been more influential and impactful than Zero Suicide (see discussion by [38]).

Recommended Standard Care

There has been little guidance about how to best meet clinical expectations for effective care of suicidal patients. In the United States, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) sponsored a working group to develop affordable and evidence-based approaches to working with suicidal risk across outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department settings. The “Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe” document [53] recommends basic approaches to working with suicidal patients, primarily emphasizing: identification/assessment of risk, stabilization/safety planning, lethal means safety discussions, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, and caring contact follow-up (all addressed throughout this article).

The Pursuit of Suicidal Typologies

Since the birth of suicide research, the determined pursuit of suicidal typologies has been a major focus of the field. Perhaps the most notable initial attempt was by sociologist Emile Durkheim in his classic work Le Suicide in 1897 [54]. Durkheim posited that there were four distinct suicide typologies as a function of social integration: egoistic, altruistic, anomic, and fatalistic. One example of this model is a World War II soldier who heroically throws himself on a live grenade within combat to save the lives of his comrades in arms—a clear example of an altruistic suicide. Many psychological typologies have ensued over the following years. In recent times, acute and chronic states have been empirically established [55]. Advanced technology has been used in ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to identify six reliable and distinct patterns of suicidal thinking [56]. Latent profile analysis can be used to identify distinct types of suicidal patients [57]. Within the realm of diagnostic nosology, Joiner and colleagues have proposed a potential DSM-6 candidate diagnosis called “Acute Suicidal Affective Disturbance” [58]. Similarly, Galynker and colleagues [59] have proposed the “Suicide Crisis Syndrome.”

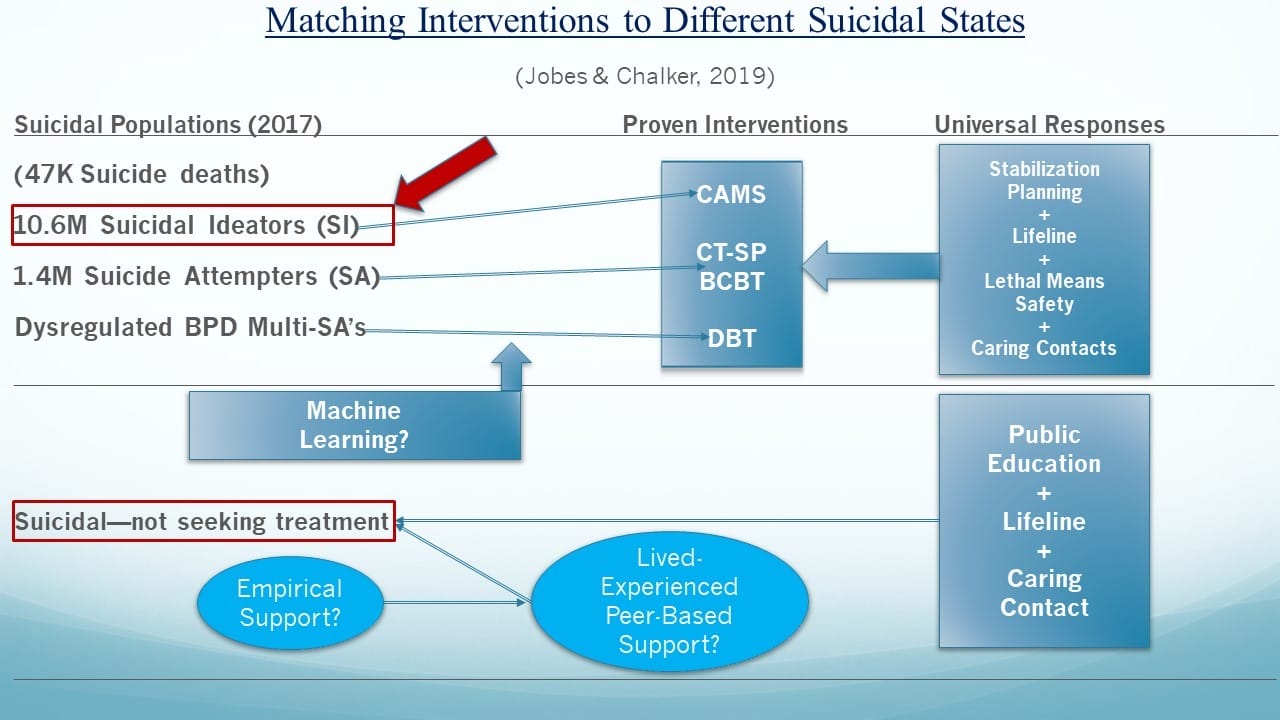

The pursuit of reliable typologies is particularly relevant when clinical treatments are considered. Indeed, Jobes argued many years ago for the pursuit of “prescriptive” treatments, that is, matching different interventions to different suicidal states [60]. The notion of routing certain suicidal patients to certain well-suited treatments was once considered a pipedream, however, the contemporary reality of this prospect is a central assertion within this article.

Machine Learning and Predicting Suicide

Another way to think about suicidal typologies is a rapidly emerging and exciting—albeit sometimes controversial—approach that is broadly referred to as “machine learning” (which is sometimes referred to as “big data” research). As described by Kessler, et al. [61], the goals of “precision medicine” are to understand how the effects of treatment are modified by patient characteristics and to develop “precision treatment rules” (PTRs) based on this understanding to determine which of the treatments under consideration is likely to yield the best outcome for each patient or fine-grained patient subgroup.

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K. Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2012, 19, 256–264. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K.; Brenner, L.A.; Galfalvy, H.C.; Currier, G.W.; Knox, K.L.; Chaudhury, S.R.; Bush, A.L.; Green, K.L. Comparison of the Safety Planning Intervention with Follow-up vs. Usual Care of Suicidal Patients Treated in the Emergency Department. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 894–900.

- Rudd, M.D.; Joiner, T.E.; Rajab, M.H. Treating Suicidal Behavior: An Effective, Time-Limited Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004.

- Bryan, C.J.; Corso, K.A.; Neal-Walden, T.A.; Rudd, M.D. Managing suicide risk in primary care: Practice recommendations for behavioral health consultants. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 148. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Mintz, J.; Clemans, T.A.; Burch, T.S.; Leeson, B.; Williams, S.; Rudd, M.D. Effect of crisis response planning on patient mood and clinician decision making: A clinical trial with suicidal US soldiers. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 69, 108–111. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Mintz, J.; Clemans, T.A.; Leeson, B.; Burch, T.S.; Williams, S.R.; Maney, E.; Rudd, M.D. Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in US Army Soldiers: A randomized clinical trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 212, 64–72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, M.D.; Bryan, C.J.; Wertenberger, E.G.; Peterson, A.L.; Young-McCaughan, S.; Mintz, J.; Williams, S.R.; Arne, K.A.; Breitbach, J.; Delano, K.; et al. Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts in a military sample: Results of a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 441–449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, M.D.; Mandrusiak, M.; Joiner, T.E. The case against no-suicide contracts: The commitment to treatment statement as a practice alternative. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 243–251. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobes, D.A. Managing Suicidal Risk: A Collaborative Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Jobes, D.A. Managing Suicidal Risk: Second Edition: A Collaborative Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Motto, J.A.; Bostrom, A.G. A randomized controlled trial of post crisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 828–833. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reger, M.A.; Luxton, D.D.; Tucker, R.P.; Comtois, K.A.; Keen, A.D.; Landes, S.J.; Matarazzo, B.B.; Thompson, C. Implementation methods for the caring contacts suicide prevention intervention. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pr. 2017, 48, 369–377. [CrossRef]

- Luxton, D.D.; June, J.D.; Comtois, K.A. Can post discharge follow-up contacts prevent suicide and suicidal behavior? Crisis 2012, 46–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comtois, K.A.; Kerbrat, A.H.; DeCou, C.R.; Atkins, D.C.; Majeres, J.J.; Baker, J.C.; Ries, R.K. Effect of augmenting standard care for military personnel with brief caring text messages for suicide prevention: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 474–483.[PubMed]

- Carey, B. Expert on mental illness reveals her own struggle. New York Times. Available online: https://www.sadag.org/images/pdf/expert%20own%20fight.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Hogan, M.F.; Grumet, J.G. Suicide prevention: An emerging priority for health care. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1084–1090. [CrossRef]

- Dimeff, L.A.; Jobes, D.A.; Chalker, S.A.; Piehl, B.M.; Duvivier, L.L.; Lok, B.C.; Zalake, M.S.; Chung, J.; Koerner, K. A novel engagement of suicidality in the emergency department: Virtual Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bruffaerts, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; Hwang, I.; Chiu, W.T.; Sampson, N.; Kessler, R.C.; Alonso, J.; Borges, G.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; et al. Treatment of suicidal people around the world. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 64–70. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.J.; Haugland, G.; Ashenden, P.; Knight, E.; Brown, I. Coping with thoughts of suicide: Techniques used by consumers of mental health services. Psychiatr. Serv. 2009, 60, 1214–1221. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.H.; Carpenter, D.; Sheets, J.L.; Miccio, S.; Ross, R. What do consumers say they want and need during a psychiatric emergency? J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2003, 9, 39–58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre, R.T.P.; Slater, H.M. Suicide postvention as suicide prevention: Improvement and expansion in the United States. Death Stud. 2010, 34, 529–540. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begley, M.; Quayle, E. The lived experience of adults bereaved by suicide: A phenomenological study. Crisis 2007, 28, 26–34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Force, S.A. The Way Forward: Pathways to Hope, Recovery, and Wellness with Insights from Lived Experience; National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Crisis Now. 2019. Available online: https://crisisnow.com (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Live Through This. 2019. Available online: https://livethroughthis.org (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Now Matters Now. 2019. Available online: https://www.nowmattersnow.org (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- MacLean, S.; MacKie, C.; Hatcher, S. Involving people with lived experience in research on suicide prevention. CMAJ 2018, 190, S13–S14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Alert: Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings. Jt. Comm. 2016, 56, 1–7.

- Brodsky, B.S.; Spruch-Feiner, A.; Stanley, B. The zero suicide model: Applying evidence-based suicide prevention practices to clinical care. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zero Suicide. 2019. Available online: https://zerosuicide.sprc.org (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- National Suicide Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: Transforming Health Systems Initiative Work Group. Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe; Education Development Center, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Durkheim, E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology, 1987; Spaulding, J.A.; Simpson, G., Translators; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1951.

- Conrad, A.K.; Jacoby, A.M.; Jobes, D.A.; Lineberry, T.W.; Shea, C.E.; Arnold Ewing, T.D.; Schmid, P.J.; Ellenbecker, S.M.; Lee, J.L.; Fritsche, K.; et al. A psychometric investigation of the suicide status form II with a psychiatric inpatient sample. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2009, 39, 307–320. [PubMed]

- Kleiman, E.M.; Turner, B.J.; Fedor, S.; Beale, E.E.; Huffman, J.C.; Nock, M.K. Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 726. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, J.S. Typologies of Suicidal Patients Based on Suicide Status Form Data. Ph.D. Thesis, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Stanley, I.H.; Rufino, K.A.; Rogers, M.L.; Ellis, T.E.; Joiner, T.E. Acute suicidal affective disturbance (ASAD): A confirmatory factor analysis with 1442 psychiatric inpatients. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 80, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Galynker, I.; Yaseen, Z.S.; Cohen, A.; Benhamou, O.; Hawes, M.; Briggs, J. Prediction of suicidal behavior in high risk psychiatric patients using an assessment of acute suicidal state: The suicide crisis inventory. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 147–158. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobes, D.A. The challenge and the promise of clinical suicidology. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1995, 25, 437–449. [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Chalker, S.A.; Luedtke, A.R.; Sadikova, E.; Jobes, D.A. A preliminary precision treatment rule for collaborative assessment and management of suicidality relative to enhanced care-as-usual in prompting rapid remission of suicide ideation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019. [CrossRef]