In recent years I have spoken, published, and blogged about the relative importance of suicidal ideation as a public health concern that does not get the proper health concern of the public. A couple of other reminders came up just last week that again underscores the need to fundamentally shift our focus to appreciating the magnitude of the suicidal ideation population, which is 225 times greater than the population of those that die by suicide.

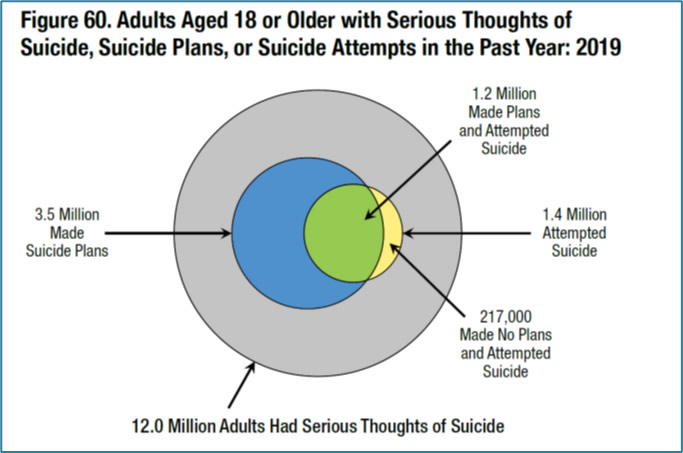

I was reviewing the most recent 2019 data from SAMHSA about the incidence of suicide-related concerns among American adults that calendar year. Take a close look at Figure 60 from the SAMHSA report—does anything particularly strike you?

As I look at this figure my eyes are naturally drawn to the highlighted blue, green, and yellow regions that respectively reflect those who made suicide plans, those who made plans and attempted suicide, those who attempted suicide, and finally those who made no plans and attempted suicide (not sure how that works exactly but such are the data).

But upon some reflection, what jumps off the page to me is that the outer circle depicts 12,000,000 American adults with serious thoughts of suicide which is not highlighted, earning only a modest gray coloring. This SAMHSA report figure thus completely fails to highlight the true objective magnitude of our suicide ideation challenge!

My question is: Why is this population graphically trivialized in this figure? In truth, 12M Americans is a massive population, roughly the size of the state populations of Pennsylvania or Illinois. If we are truly examining the challenge of suicide as a public health issue, we of course care deeply about 48,000+ of Americans who died by suicide in 2018, and the 1.4M attempting suicide in 2019 is extremely concerning as well – but frankly these populations are utterly dwarfed by the massive suicide ideation population. And it logically follows that if we were better at identifying and treating this gigantic population, we may have many fewer attempts and ultimately many fewer completions. Right?

As I recently blogged, I have been honored to be a part of a small team that is working to write an addendum to the 2018 Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe promulgated by the National Alliance for Suicide Prevention. This draft addendum focuses on the apparent inclination of some health care systems to discontinue or suspend screening and assessment of suicidal risk since the Covid-19 pandemic which has driven our health care to online/telehealth modalities. In the forthcoming addendum there is a reassertion that even within telehealth there is a reasonable way to screen and assess for suicide risk (even if this is done asynchronously). In the addendum we have argued that not asking about suicide is no way to go about actually preventing suicides. After all, it is hard to save lives if we do not know that patients are at risk.

Here is the point: in my final review of the carefully written document our language tended to emphasize depression and suicidal behaviors, not even mentioning the importance of suicidal ideation. Even I, who have held these beliefs for some time, completely missed this omission in early drafts!

Mind you, depression and suicide are not synonymous; out of the 132 Americans that die from suicide each day in the U.S., roughly half may be clinically depressed (many others will be psychotic, anxious, substance abusing, personality disordered, etc.). In other words, depression is not even remotely the cause of many of our suicides since millions of Americans are clinically depressed and only a small fraction of them die by suicide.

In my final review of our addendum I made edits to de-emphasize depression and suicidal behaviors in lieu of emphasizing suicidal ideation, particularly as it relates to screening and assessment within a telehealth modality during a worldwide pandemic. I am pleased to note that while depression remains in the document, we have properly underscored the import of suicidal ideation and cited the SAMHSA paper noted above.

This is not going to be the last time that I appeal for us to recalibrate our suicide prevention policy, research, and clinical care focus to stop this peculiar bias to overly focusing on suicidal behaviors while dangerously disregarding suicidal ideation. My journal papers should not be rejected because CAMS “only” reduced suicidal ideation. Indeed, I would note within the clinical treatment research that other excellent suicide-focused interventions (e.g., DBT, CT-SP, and BCBT) do not reliably reduce suicidal ideation like CAMS does. However, these interventions more reliably reduce suicide attempts (while CAMS has only promising behavioral data thus far). The clinical trial data to date are exactly why I have strongly argued against a “one size does not fit all” approach to care for suicidal risk.

So, I am going to keep on banging the suicide ideation drum, appealing to those in our field to more completely consider the import and magnitude of the suicidal ideation population. In truth, if we truly aim to reduce completed suicides, our research, practices, and policies must better target and treat the underlying iceberg of suicidal ideation so as to reduce the tip above the water of suicide attempts and ultimately deaths by suicide.