Disclaimer: In this article, I use identity-first language when referring to autism rather than person-first language (autistic person vs person with autism). In the adult autistic community, we use this language because 1) being autistic is a part of our identity, and 2) autism is not a disorder. For more information about terminology check out this article on identity-first language by the Autism Network: https://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/identity-first-language/

Think of the word: autism. What image comes to mind? How would you describe an autistic person? Would you say they’re socially awkward, low empathy, genius, or weird? Or maybe you imagine an awkward, pompous nerd – one who unintentionally says the most inappropriate things, but means well. Like Sheldon from ‘The Big Bang Theory’ or Dr. Shaun Murphy from ‘The Good Doctor’. This stereotype of the autistic person is reductive, exaggerated, and harmful to the diversity and complexities of the adult autistic community.

This characterization was originally invented during WWII, when a Nazi eugenicist named Hans Asperger identified a subset of characteristics that explained the symptomatology of research subjects.[1] He began his experimentation on ‘undesirables’ or disabled children. Asperger discovered a subset of disabled boys who presented as antisocial and ‘lacking empathy’, but having advanced intellectual capabilities. These children were used as the perfect subjects for his discovery of Asperger’s Syndrome, and those who did not fit into his characterization were euthanized.[2] The term and diagnosis of Aspergers is no longer used within the DSM-5-TR (and Aspergers has been integrated into the autistic diagnosis). However, the characterization of autism as a ‘genius’ disorder that only affects white boys has persisted and gained popularity since the 90’s. While some autistics are white, male geniuses, it is not the whole spectrum of our identities. We represent the collective diversity that is present in the world. In fact, a vast majority of autistic individuals identify as LGBTQ, are women and/or non-binary.[3] Some of us are a part of the High IQ society, while others struggle with math. Some of us love trains, while others are obsessed with lining up their barbie dolls or are die-hard thespians. Autistic people come in a variety of identities, and to limit these complexities, hinders the assessment, support, and resources we receive as adults. In this article, we will examine the challenges autistic adults experience and the types of support adult autistic individuals need to improve functionality.

What is autism?

- Autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neuro-developmental condition that impacts the way a person communicates, perceives, and interacts with the world around them.[4] Autistic traits include the below, though there are numerous other tendencies that can be described as autistic lack of eye contact

- an interest in select special interest

- (repetitive, reflexive movements used to self-regulate or express joy; E.g. arm flapping or humming)

- Following rigid routines

- Prone to meltdowns and over stimulation

- Difficulty understanding subtext in communication (takes things literally)

Autism is not a mental health disorder nor a disease; although mental disorders and physical disabilities do co-occur.[5] In more simplistic terms, autism is a different way of functioning and perceiving the world. For non-autistics (or neurotypical individuals), autistic people are perceived as ignoring social norms, lacking social competency, and communicative skills. However, to us, our functioning is a normal way we interact with the world. From our perspective, we adhere to our moral compass, communicate directly, and our intentions are genuine. Autistics are not asking to be fixed. They are asking for understanding, support, and resources to improve their functionality in a world that is not designed for them. Without these supportive systems, autistic adults face a multitude of challenges that lead towards factors of trauma, alienation, and abuse.

5 Common Challenges Faced by Autistic Adults

-

Substance Addiction

Research suggests that 50% of autistic adults develop substance addiction within their lifetime.[6] Drugs, alcohol, and other substances both alter behavioral responses and coping mechanisms. From one angle, substances can be a barrier against the anxieties of strenuous, social interactions. An autistic adult who is perceived as ‘socially awkward’ and ‘withdrawn’ while sober, may become the life of the party (or at least socially ‘normal’) while in an altered state. This allows the person to mask—a coping mechanism for autistic people where they interact with others using neurotypical behaviors. From another angle, substances are also a coping mechanism in helping autistic adults deal with the long-term effects of bullying, trauma, and loneliness.

-

Suicidality & Shorter Life Expectancy

Death by suicide is three times higher in autistic adults than in the general population.[7] For autistic women the rates of suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-harm is even higher. [8] As previously discussed, autistic adults have a lifetime of experiences with childhood bullying, which leads to adult trauma. These traumas are often comorbid with anxiety, depression, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD). [9] As the NIH research shows, these co-occurring with psychological disorders increases an autistic adult’s risk of suicidal ideation. Individuals experiencing comorbid anxiety disorders in tandem with autism will often experience higher suicidal risk, and be more susceptible to its effects

Autistic adults have lower life expectancy in comparison to the general population.[10] The average age expectancy for an autistic adult is 36 years. What’s causing these premature deaths? A few risk factors leading to premature deaths in autistic adults are linked to systemic discrimination, chronic disabilities, and economic challenges. We are more likely to be unemployed and live below the poverty line. In fact, over 60% of autistic adults are unemployed.[11] Circumstances that are impacted by employment consist of hardships within the job application, interview, and hiring process. In addition, we are more likely to have chronic disabilities, such as autoimmune disorders, chronic inflammation (which can lead to cancer), and other health problems that are linked to lower life expectancy. [12]

-

Childhood Bullying & Abusive Adult Relationships

Over 60% of autistic children and teens experience bullying. [13] The long term effects of bullying include, but are not limited to: low self-esteem, trust issues, social isolation, relational problems, depression, and anxiety. These long term effects continue into adulthood.

As adults, many autistic individuals (especially women) experience abusive intimate partner relationships. An alarming study conducted in 2022 found that 9 out of 10 autistic women experienced sexual assault. [14] Many abusers prey on individuals who are disabled, and autistic people are an easy target due to our neurological wiring and alienation. Autistic adults tend to be more trusting of people and may not recognize red flags/toxic behavior, due to a history of trauma and people-pleasing tendencies.

-

Misdiagnosis

Within the autistic community and neurodivergent-affirming therapeutic spaces, self-diagnosis as autistic is valid. For autistics within underserved communities (i.e., BIPOC, LGBTQ, women, etc…) official and early diagnosis has been inaccessible, unaffordable, and misdiagnosed. Autistic individuals have been misdiagnosed with mental disorders such as bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia, antisocial personality disorder, and other mental health functionalities.[15] As discussed earlier, autistic behaviors present differently within each individual and sometimes behaviors are similar or co-occur with diagnostic criteria of mental disorders. Sometimes autistic behaviors are overlooked by family members or providers based on societal biases. For example, autistic behaviors in boys are often categorized by ‘antisocial’ or withdrawn behavior. However, many young girls and women are socialized to be more socially adaptable and are ‘better” at masking autistic traits. For many marginalized groups, masking is a normalized response to systemic disparities.[16]

-

Lack of Adult Resources & Support

ASD is officially diagnosed in childhood through a lengthy evaluation process, which contains parent/teacher interviews, psychological assessments, and clinical observations. There are no adult assessments, so assessments are based on the same criteria as the children’s assessments. Many of my autistic clients have shared, they find the assessment process to be intrusive and alienating. Those who are estranged from their bio families, have difficulties with the parent interview process. Diagnostic rates range from $1,000 and up, which eliminates individuals with low socioeconomic status.

Once diagnosed, adult autistics are left without support in understanding their diagnosis, finding community, or navigating their daily lives. As with childhood diagnoses, often the only referral service is Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) therapy. For adult advocates, community members, and professionals (like myself) ABA is an abusive treatment practice. Founded by the misguided creator of gay conversion therapy, ABA is a treatment that uses extreme compliance and erasure of autistic autonomy, enforcing normative behavior by repressing ‘undesirable’ autistic traits (i.e. stimming, natural coping strategies for overstimulation, etc…).[17] For example, a child who is lashing out by screaming and hitting themselves is perceived as destructive. In ABA, the why is not addressed. A course of negative reinforcement, by way of restricting stimming (self-soothing, autistic behaviors) and the autistic child’s favorite things is the treatment. Eventually the child stops the destructive behavior and everyone moves on. Except, the basis for the meltdown continues and the child internalizes their autistic traits. If we deconstruct the autistic child’s behavior from a neurodivergent affirming framework, our treatment plan centers the child’s needs, autonomy, and self-confidence. Autistic adults who had ABA therapy as children self-reported and current research studies show the long-term effects of ABA include increased depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms.[18]

[When an autistic child is experiencing sensory overload, they experience meltdowns that include hitting themselves, biting, screaming, and other non-verbal behaviors. This behavior is called an autistic meltdown and the best approach to stopping the behavior, is to remove the child from the stimulant. As a child, I would often become overstimulated by overhead lights or intense sounds (family gatherings). I could not articulate what I was experiencing and would fall into meltdowns of epic proportions. As a late-diagnosed adult, I can finally comprehend that I am overstimulated and take measures to reduce my discomfort. Noise-cancelling headphones or temporarily moving to a quiet area has increased my autonomy and interpersonal relationships. However, for a child (especially non-verbal, autistic children) communicating these discomforts is impossible and is often punished rather than supported.]

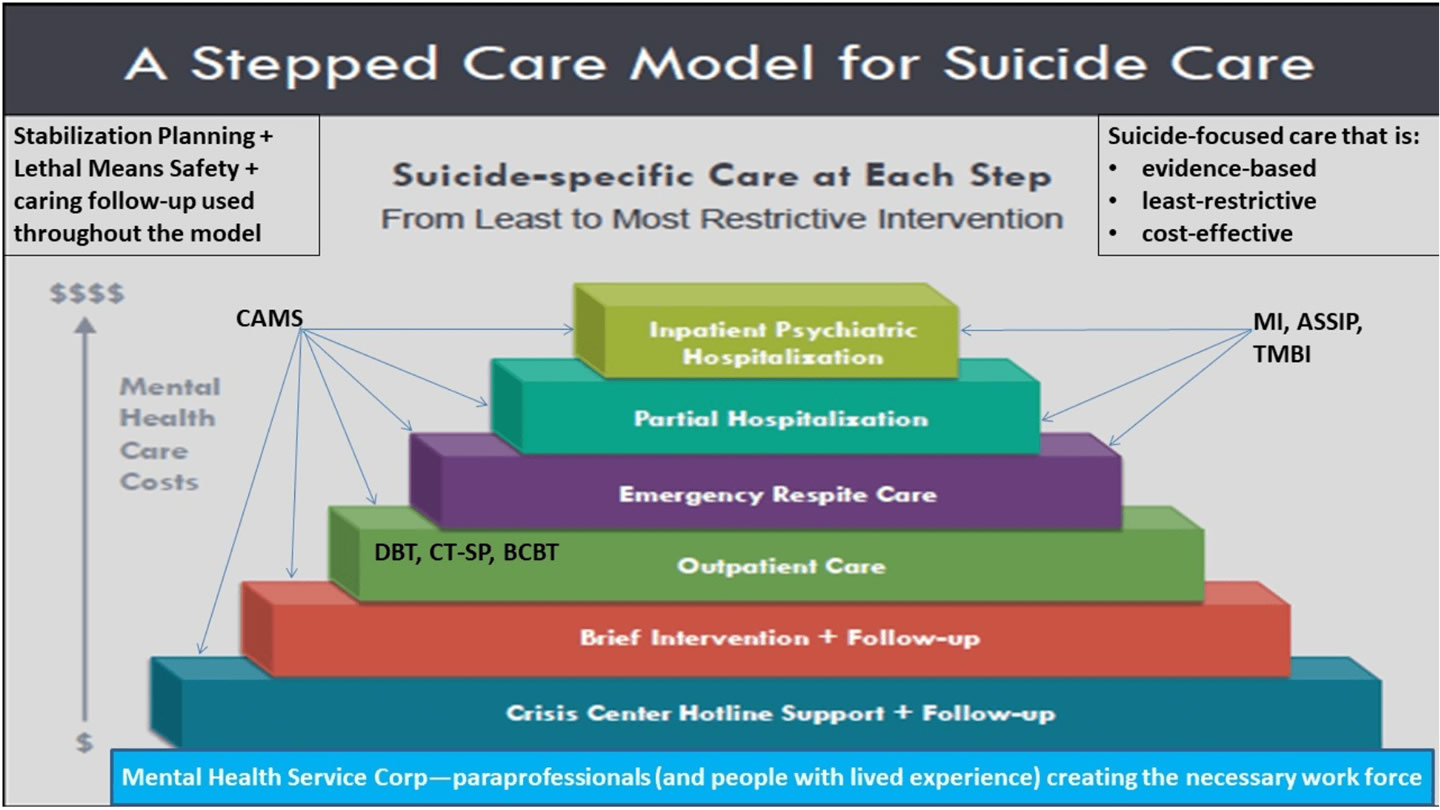

A Modified-CAMS Autistic Approach

The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) is an evidence-based therapeutic approach using randomized control trials as an effective approach to decreasing suicidal risk across a diverse range of clients.[19] We autistic individuals tend to love concise, clear, and organized information. In my professional opinion, the effectiveness of CAMS in articulating direct questions and organization through the Suicide Status Form (SSF), makes CAMS an effective framework to support autistic teens and adults. Below, I have compiled a list of 3 ways CAMS can be modified to directly support autistic individuals. [These suggestions can also be applied to general therapeutic practices].

-

Use a Direct, Concise Approach

As I have discussed, autistic people often need concise, direct language when communicating. It is imperative for the provider to use direct language, due to the communication barriers that are frequently presented in conversations between neurotypical and autistics. For example, when a neurotypical question such as “how are you feeling?” is asked, a neurotypical person might say, “I’m feeling sad”. For many autistic people this question is not direct because it can be applied to a number of factors (I.e., how I’m feeling in the present moment, or how I’m feeling regarding interacting with you, or even how I’m feeling regarding the weather). Another factor to consider is that some autistics have alexithymia—an inability to identify and describe emotions. Often when asked about emotional states an autistic person might respond by saying “I don’t know” or even state an emotion that is opposite of what they are feeling. When filling out the SSF with the client, ask questions that are concise, but also describe what you mean, such as, “when you think about dying by suicide, where in the body do you feel it?” or “do you have a plan to die by suicide?”.

-

Be Open to Unconventional Support Systems

For many autistics, making and maintaining relationships is extremely difficult – and adult relationships especially. In addition to communication difficulties, factors such as emotional dysregulation and rejection sensitivity makes interpersonal relationships almost impossible. Due to a history of trauma, it can be hard for autistic individuals to reach out for support. Even greater, due to limited resources, support can be inaccessible. When discussing external support systems with a client, providers must ‘think outside the box’. This may look like finding external support through adult autistic online communities, support groups, or social media spaces. Or creating a support plan that includes non-family systems such as friends, neighbors, and fellow providers.

-

Respect Their Autonomy

If I gained a quarter for every time someone spoke to me as if I was a child or incapable of making decisions, after disclosing I’m autistic to a provider, well I could retire. The spectrum of functionality of autistic people is so broad, that one autistic adult might have challenges with motor skills (dyspraxia), while another has difficulty with word processing (dyslexia). No two autistic individuals are similar and we are not a monolith. To support autistic clients is to 1) trust they are the expert on their own experience and 2) functionality difficulties are different in each individual.

Finding support for autistic adults is universally inaccessible to many underserved communities. Many medical and mental health providers are not versed in providing evidence-based, neurodivergent-affirming treatment. They do not receive training on recognizing autistic traits nor how to interact with autistic adults. It makes seeking medical and mental health support problematic. Navigating the challenges of dating, sex, employment, and all the other complexities of adulthood becomes an impossible reality for unsupported autistic adults. Which leads to increased burnout, meltdowns, and mental health tragedies.

References

[1] Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity by Steve Silberman

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/31/opinion/sunday/nazi-history-asperger.html

[3] https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/autistic-individuals-are-more-likely-to-be-lgbtq

[4] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6225088/

[5] https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2017/03/autism-and-addiction/518289/

[6] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2774847

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6457664/

[8] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6225088/

[9] https://www.cnn.com/2017/03/21/health/autism-injury-deaths-study/index.html

[10] https://drexel.edu/~/media/Files/autismoutcomes/publications/LCO Fact Sheet Employment.ashx

[11] https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/autistic-adults-have-a-higher-rate-of-physical-health-conditions

[12] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/survey-finds-63-of-children-with-autism-bullied/

[13] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9087551/

[15] https://www.aane.org/women-asperger-profiles/

[16] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9114057/

[17] https://neuroclastic.com/invisible-abuse-aba-and-the-things-only-autistic-people-can-see/

[18] https://cams-care.com/about-cams/the-evidence-base-for-cams/