Please note the following post uses identity-first language, though acknowledges that preferences may differ between self-advocates.

Background

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a developmental disorder characterized by ongoing differences and challenges in social communication and restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Research has highlighted increased early death in autistic individuals, and suicide is a primary cause (Cassidy et al., 2014). Autistic adults are at increased risk for suicide compared to non-autistic adults (Hedley et al., 2017). In a study of a large, diverse population of adults in the United States, the risk of suicide attempts was five times higher for autistic adults than for non-autistic adults (Croen et al., 2015). While suicide research has largely focused on autistic adults so far (McDonnell et al., 2020), autistic youth are also more likely to attempt and die by suicide (Navaneelan, 2012). A study of autistic individuals aged 4-20 years evaluated during a psychiatric hospital stay found that 22% of autistic youth commonly talked about death or suicide (Horowitz et al., 2018). While studies differ about exact prevalence rates, experts agree that there is reason for concern.

Despite the increase in research and autistic self-advocacy groups’ attention on this topic, there continues to be a major lack of tools to manage suicidal behaviors in the autistic population. Therapists feel less confident providing care to autistic individuals experiencing suicidal thoughts (Jager-Hyman et al., 2020). The good news is that there are efforts to validate screening tools for use with autistic adults, including screeners (e.g., SBQ-ASC, SIDAS-M, STUQ), and more in-depth assessment tools such as the Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview (Hedley et al., 2025). However, these tools are designed for adults, and there are not yet appropriate for autistic youth. This is important when considering existing screening tools, given that autistic individuals may not always exhibit traditional suicide symptoms and warning signs. For example, autistic individuals may present with facial expressions which may not directly match their emotional experience (e.g., laughter when anxious or depressed) or have difficulty verbalizing their thoughts, feelings, and experiences when overwhelmed (Oliphant et al., 2020).

While quality access to mental health services is a problem for all children and adolescents, this challenge is worse for autistic individuals and their families (Cervantes et al., 2023). In fact, many providers do not accept autistic patients. In a study of over 6,000 outpatient mental health facilities in the United States, only half offered services to autistic children (Cantor et al., 2022), which is particularly concerning given this group’s increased mental health care needs. When these needs go unmet, autistic youth are more likely to present to Emergency Departments (EDs) (Badgett et al., 2023). Unfortunately, EDs and psychiatric hospitals are not designed for autistic individuals’ needs from both an environmental perspective (e.g., sensory sensitivities to bright lights, crowdedness, unpredictability) and a treatment standpoint (e.g., stigma related to mental health in medical settings, lack of training related to autistic learning styles, and behavior management techniques). Sadly, this can then lead to negative or traumatic experiences, inappropriate treatments, excessive interventions (e.g., physical or chemical restraints, seclusion), and longer admissions (Gabriels et al., 2012; Klinepeter et al., 2024).

Adapting evidence-based suicide-focused treatments, such as Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) (Ritschel et al., 2022) and Safety Planning Intervention (Rodgers et al., 2023), remains an area of emerging research. Therefore, evidence-based suicidality treatment made for autistic individuals is a sparsely available, yet urgently needed service.

Clinical Insights

Unfortunately, many of the clinicians who treat suicidality or autism remained siloed in their respective treatment areas, without clear communication and overlap, despite extensive research and clinical experience on both sides. To treat suicidality in autism, it is necessary that these “worlds” collaborate, create synergistic relationships, and develop treatments to address this life-threatening phenomenon.

Recent work has suggested that some general changes to treatments can be helpful for autistic learning styles, such as visual supports, environment and sensory considerations, making language more concrete, caregiver collaboration, and embedding special interests into treatment (Schwartzman et al., 2021; Dickson et al., 2021).

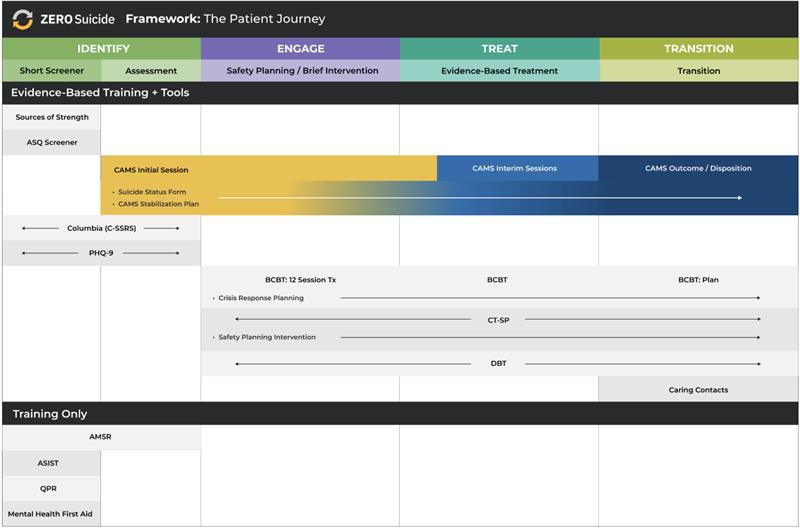

As a result of this critical gap in services, a clinic was created to treat suicidality in autistic youth at a large children’s hospital, the Clinic for Autism and Suicide Prevention (CLASP). As mentioned above, collaboration between the autism center and the hospital’s department of behavioral and mental health was necessary and invaluable. The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS was) incorporated as the primary treatment framework when appropriate, and autism-specific interventions were then plugged in to address specific drivers. The CAMS Framework® identifies the “drivers” that a patient says make them consider suicide as an option.

For example, if a patient identified difficulty with change as a driver, an autism intervention, such as Unstuck and on Target, was used. If a patient identified loneliness as a driver, then social skills practice or PEERS videos were incorporated to improve relationships. Additionally, interventions such as cognitive behavior therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy were often used to address many other drivers such as conflict with others, traumatic experiences, or difficulty managing strong emotions.

The clinic provides individual weekly therapy to autistic youth experiencing suicidality and has successfully discharged several patients due to reduced suicidality. We have learned many key insights from this clinic and from the powerful, brave work these patients are doing. Below are some recommendations for working with autistic clients who experience suicidality.

Recommendations for clinical practice:

- Consider whether there are outside factors which can be addressed or managed. For example, if a patient is struggling with bullying, consider whether school can intervene. Remember that autistic are neurodivergent individuals living in a world designed for neurotypical needs!

- Take your time and expect that treatment progress may take longer. Negative repetitive patterns can be “stickier” in autistic individuals and breaking out of these cycles can require more effort and time.

- Create structure when possible. CAMS forms (e.g., the Suicide Status Form, the Stabilization Support Plan for parents and caregivers and the CAMS Therapeutic Worksheet) are a great way to introduce a visual form and help clients know what to expect from session to session.

- Determine whether expressing suicidal thoughts is a form of communication and if so, consider what the patient is communicating and whether this can be addressed. For example, if a patient repeatedly makes suicidal comments when transitioning away from a preferred activity (e.g., video game, favorite location), consider working on transitions with behavioral strategies. Think about whether there are other ways the patient can communicate their frustration.

- Discuss what happens both for the patient and others when they share suicidal thoughts. First, understand what the patient is feeling and why they are sharing. Next, while openness is important, some individuals may not be aware of the procedures certain organizations have to follow when someone makes a suicidal comment (e.g., school policies, medical staff) and explaining what to expect can help reduce emotional overload.

- Help increase emotional awareness. In some autistic clients, the ramp up to a crisis moment can be much faster than in non-autistic individuals, so increasing emotional self-monitoring can improve their ability to access coping strategies earlier.

- Do not assume that physical social or human contacts are the only way to reduce suicidal risk. Perhaps there are other non-human or non-physical connections which can be important for coping, such as a preferred stimming object, online video game friends, or an important pet. Stimming (i.e., repetitive self-soothing movements, such as pacing, rocking, humming, finger tapping) can be helpful both during therapy and as part of a stabilization plan.

- Do not assume that all autistic patients need autism-specific treatments. This can create barriers and close important doors to care. Some autistic patients benefit from working with clinicians experienced in autism, though this is not necessary for every patient. Our saying is “when you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person!”

Most importantly, remember that autistic clients often have amazing and powerful insight into their emotional experiences that leads to suicidality. Start with the patient perspective first, gather additional information, and empower the client to work collaboratively toward a life worth living one small step at a time!

Below are several helpful resources available online including those developed by autistic self-advocates:

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edition). Arlington, VA: Author.

Badgett, N. M., Sadikova, E., Menezes, M., & Mazurek, M. O. (2023). Emergency department utilization among youth with autism spectrum disorder: exploring the role of preventive care, medical home, and mental health access. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(6), 2274-2282.

Cantor, J., McBain, R. K., Kofner, A., Stein, B. D., & Yu, H. (2022). Where are US outpatient mental health facilities that serve children with autism spectrum disorder? A national snapshot of geographic disparities. Autism, 26(1), 169-177.

Cassidy, S., Bradley, P., Robinson, J., Allison, C., McHugh, M., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2014). Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with Asperger’s syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: a clinical cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(2), 142-147. https://10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70248-2

Cervantes, P. E., Conlon, G. R., Seag, D. E., Feder, M., Lang, Q., Meril, S., … & Horwitz, S. M. (2023). Mental health service availability for autistic youth in New York City: An examination of the developmental disability and mental health service systems. Autism, 27(3), 704-713.

Klinepeter, E. A., Choate, J. D., Nelson Hall, T., & Gibbs, K. D. (2024). A “whole child approach”: parent experiences with acute care hospitalizations for children with autism spectrum disorder and behavioral health needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1-15.

Croen, L., Zerbo, O., Qian, Y., Massolo, M., Rich, S., Sidney, S. & Kripke, C. (2015). The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19(7), 1-10. https://doi/abs/10.1177/1362361315577517

Gabriels, R. L., Agnew, J. A., Beresford, C., Morrow, M. A., Mesibov, G., & Wamboldt, M. (2012). Improving psychiatric hospital care for pediatric patients with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. Autism research and treatment, 2012(1), 685053.

Hedley, D., Uljarević, M., Wilmot, M., Richdale, A., & Dissanayake, C. (2017). Brief report: social support, depression and suicidal ideation in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3669-3677. https://10.1007/s10803-017-3274-2

Hedley, D., Williams, Z. J., Deady, M., Batterham, P. J., Bury, S. M., Brown, C. M., … & Stokes, M. A. (2025). The Suicide Assessment Kit-Modified Interview: Development and preliminary validation of a modified clinical interview for the assessment of suicidal thoughts and behavior in autistic adults. Autism, 29(3), 766-787.

Horowitz, L. M., Thurm, A., Farmer, C., Mazefsky, C., Lanzillo, E., Bridge, J. A., Greenbaum, R., Pao, M., & Siegel, M. (2018). Talking about death or suicide: Prevalence and clinical correlates in youth with autism spectrum disorder in the psychiatric inpatient setting. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(11), 3702-3710. https://10.1007/s10803-017-3180-7

Jager-Hyman, S., Maddox, B. B., Crabbe, S. R., & Mandell, D. S. (2020). Mental health clinicians’ screening and intervention practices to reduce suicide risk in autistic adolescents and adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3450-3461.

McDonnell, C. G., DeLucia, E. A., Hayden, E. P., Anagnostou, E., Nicolson, R., Kelley, E., … & Stevenson, R. A. (2020). An exploratory analysis of predictors of youth suicide-related behaviors in autism spectrum disorder: implications for prevention science. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3531-3544. https://10.1007/s10803-019-04320-6

Navaneelan, T. (2012). Suicide rates: An overview. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada.

Oliphant, R. Y., Smith, E. M., & Grahame, V. (2020). What is the prevalence of self-harming and suicidal behaviour in under 18s with ASD, with or without an intellectual disability?. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(10), 3510-3524.

Ritschel, L. A., Guy, L., & Maddox, B. B. (2022). A pilot study of dialectical behaviour therapy skills training for autistic adults. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 50(2), 187-202.

Rodgers, J., Goodwin, J., Nielsen, E., Bhattarai, N., Heslop, P., Kharatikoopaei, E., … & Cassidy, S. (2023). Adapted suicide safety plans to address self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide behaviours in autistic adults: protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. Pilot and feasibility studies, 9(1), 31.