By: Dr. Dave Jobes

I am delighted to blog about a brand-new meta-analysis of nine clinical trials showing robust support for the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS). This landmark article has just been published in the suicide prevention field’s premier peer-reviewed scientific journal, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior.

The CAMS meta-analysis project was led by Dr. Joshua Swift, a well-established psychotherapy treatment researcher, and Associate Professor of clinical psychology at Idaho State University (ISU). Dr. Swift, along with two graduate students, pursued a rigorous meta-analysis of CAMS clinical trials during the summer of 2020, submitting their manuscript for peer-review in the fall. This meta-analysis was sponsored by CAMS-care, LLC with the goal of supporting an independent research laboratory to conduct a demanding and labor-intensive meta-analysis (which is a large study of various studies that meet certain specific selection criteria). It is noteworthy that Swift and his team are not suicide treatment researchers, which helped ensure a fresh and unbiased perspective to this rigorous scholarly undertaking.

To conduct this meta-analysis, the ISU research team identified over 1,000 published and unpublished articles, theses, and dissertations that referred to “CAMS” or “SSF” (the Suicide Status Form is a multipurpose assessment and treatment tool used within CAMS). Using certain selection criteria (e.g., empirical clinical trial data vs. conceptual; having a comparison control group design vs. no control comparison), the team eventually identified and selected nine clinical trials of CAMS comparing it to control treatments, such as “treatment as usual” (TAU) and one Danish trial comparing CAMS to Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). Once the selected studies were identified, the team performed a series of statistical analyses across the studies to investigate the relative effect sizes related to clinical treatment outcomes (i.e., a measure of the relative impact of the interventions on certain key outcome variables). In other words, the overall impact of study treatments within and across all the selected clinical trials can all be compared within a meta-analysis (additional analyses related to “moderator effects” were also studied).

The results of their efforts were impressive. The research team found that, in comparison to control treatments, CAMS caused significant reductions in suicidal ideation and overall symptom distress while positively impacting hope/hopelessness and increasing treatment acceptability. There was non-significant—but trending—support for its positive impact on suicidal attempts, self-harm, and cost-effectiveness (but more data are needed to see if these effects could reach statistical significance). Importantly, in none of the nine selected clinical trials of CAMS was comparison treatment ever better than CAMS when overall “weighted averages” across studies for each clinical outcome were calculated. There were no significant differences between the use of CAMS with white vs. non-white patients (but more diverse clinical samples are needed; the European CAMS studies to date have primarily had patients who were Caucasian).

Interestingly, the clinical trials in which I (as the creator of CAMS) was directly involved did relatively worse than ones in which I was not involved! Thus, there is no “publication bias” or “allegiance effects,” which underscores the scientific objective nature of the meta-analysis evidence supporting CAMS. Dr. Swift’s team ultimately concluded that CAMS is “Well Supported” as a clinical intervention for suicidal ideation as per Center for Disease Control criteria (which is the highest level of empirical support).

Review the original article by Dr. Swift: The effectiveness of the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) compared to alternative treatment conditions: A meta-analysis

So, what does all this rigorous research of various clinical trials actually mean? In short, this meta-analysis of CAMS is a breakthrough investigation that caps off almost 30 years of hard-earned clinical trial research, which first focused on the early use of the SSF that later evolved into the suicide-focused clinical intervention that CAMS has become. This meta-analysis convincingly confirms that using this suicide-focused therapeutic framework works for many patients who are suicidal around the world and in different treatment settings (e.g., outpatient settings, crisis clinics, and inpatient settings). It confirms that emphasizing the four “pillars” of CAMS—collaboration, empathy, honesty, and being suicide-focused—is indeed a proven way of reliably decreasing suicidal ideation and reducing serious psychiatric distress.

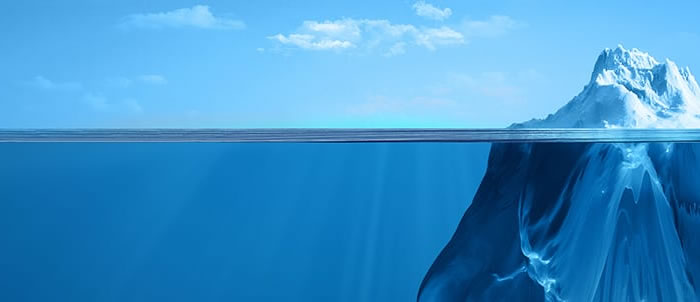

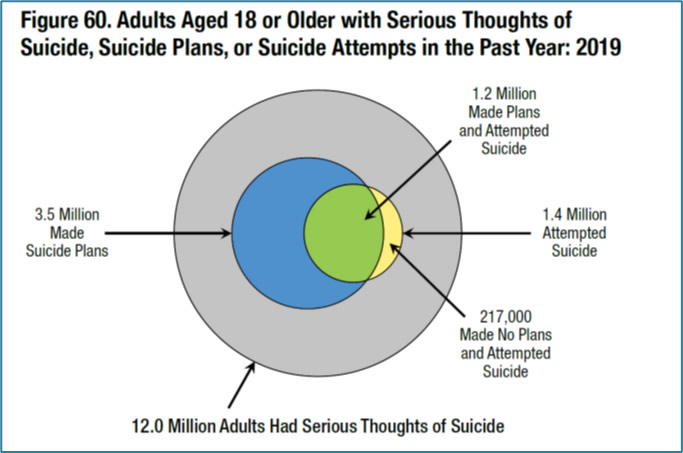

One of my favorite findings from the meta-analysis is that the most robust weighted average was for the outcome of decreasing patients’ hopelessness while increasing their hope! This is an important finding about which I have previously blogged. For me, the publication of this independent and rigorous study is a career highlight and a convincing testament to the effectiveness of CAMS for patients who are suicidal around the world across a range of clinical settings. We can now say with confidence that CAMS effectively treats the most significant challenge that we face in the field of suicide prevention today: the massive population of people who struggle with serious thoughts of suicide. Given the evidence, we believe that CAMS can effectively treat the “iceberg” of people with suicidal thoughts, a population 225 times greater than the population of those who take their life (Reflections on Suicidal Ideation). If we succeed in our efforts to train more clinicians to provide “upstream” effective CAMS-guided care to those who struggle with serious suicidal thoughts, perhaps we can help divert such patients from going on to attempt suicide or even prevent them from suicide further “downstream.” Thus, the publication of this new meta-analysis supporting the use of CAMS by Swift and colleagues is a major breakthrough to realizing the ambitious goal of reducing suicide-related suffering in all its forms around the world.

* * * * *

Background on the CAMS Framework

CAMS is a therapeutic framework for effectively treating suicidal risk. It evolved from a line of suicide risk assessment research that initially began at the University Counseling Center at The Catholic University of America in the late 1980s. The key tool in CAMS is the Suicide Status Form (SSF) which guides all clinical activity within the intervention—from the initial session, across all interim care, to the outcome/disposition session, which concludes the use of CAMS. The SSF, therefore, functions as a multipurpose assessment, treatment planning, tracking, to clinical outcome tool. Previous research has shown that the SSF serves as a “therapeutic assessment.” CAMS SSF-based treatment planning focuses on patient-identified suicidal “drivers,” which are the problems that compel them to consider suicide (e.g., a relational breakup or self-hate). CAMS, therefore, targets and treats the patient’s suicidal drivers over the course of care to achieve optimal clinical outcomes such as rapid reduction of suicidal thoughts (in as few as 6-8 sessions), decreased symptom distress, and decreased hopelessness with increased hope.

CAMS’s Purpose and Function

The purpose of CAMS is to engage a person who is suicidal in a strong therapeutic clinical alliance while increasing their motivation to be an active collaborator within their tailored suicide-focused care. CAMS thus functions as a guiding framework to help stabilize the patient’s life while suicidal drivers are addressed and treated throughout the course of care. CAMS concludes with a focus on purpose and meaning and the pursuit of a life worth living.

How Clinicians Utilize CAMS

Clinicians across a range of clinical settings use CAMS to effectively stabilize and treat patients who are suicidal. The framework is atheoretical, which means that it is not tied to a particular theoretical orientation or set of techniques. The SSF provides structure for assessing suicidal risk at the start of each session and ensures that the suicide-focused treatment plan is updated at the end of every CAMS-guided session. The SSF also helps create extensive medical record documentation that reflects effective suicide-focused assessment, treatment planning, and follow-through. This kind of documentation reflects good practice and helps decreased the risk of malpractice liability related to working with patients who are suicidal.

Why CAMS is Effective in Reducing Suicidal Ideation and Associated Issues

Research has clearly shown that when CAMS is used adherently, it reliably reduces suicidal ideation and overall symptom distress, while increasing hope, and improving retention to clinical care. While more research is needed to understand the exact mechanisms of CAMS, we believe that a strong clinical alliance along with empathy and validation are essential ingredients to all successful CAMS-guided care. Research also shows that CAMS seems to change the patient’s “relationship” to suicide, providing alternative coping methods and getting needs met. Beyond helping patients become less suicidal, CAMS also encourages patients towards the end of care to actively consider the pursuit of plans, goals, and hope for the future within a life worth living—a “post-suicidal” life—a life with purpose and meaning.

The Need for Effective Suicide Interventions

There are remarkably few proven-effective clinical treatments for patients who are suicidal. Many practitioners rely on inpatient hospitalizations and psychotropic medications which have limited to no evidence for being effective with suicidal risk. Other effective treatments like Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) or suicide-specific Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are more effective with decreasing suicide attempts, whereas CAMS reliably treats the much larger population of people with serious suicidal thoughts. Moreover, CAMS is relatively easy to learn compared to DBT and CBT and is generally more flexible and adaptable to different settings and theoretical orientations compared to other effective suicide treatments.

The Merit of CAMS is Undeniable

CAMS is a proven and effective treatment that is relatively easy to learn and ensures good practice and documentation that helps decrease practitioner exposure to liability. Research has shown that patients significantly prefer CAMS to usual care, and training in CAMS has been shown to increase provider competence and confidence, which are critical to successful care.

Case Example

In a randomized controlled trial of CAMS conducted at a U.S. Army infantry post, there was a multiply deployed Soldier “John” who came into treatment after being referred by his commander. John had significant combat-related trauma, and he was extremely upset that his ex-wife was moving to another state taking their two young sons. His CAMS clinician—a skilled clinical social worker—engaged him with the SSF in the first CAMS session. They readily identified his suicidal drivers: combat-related PTSD and the potential loss of access to his sons.

Over the course of ongoing interim CAMS care, the clinician effectively treated the Soldier’s PTSD with cognitive processing therapy (CPT). The clinician also arranged for the Soldier to meet with a JAG officer to receive legal consultation related to gaining joint child custody. Beyond treating his drivers, a significant issue with this Soldier was the clear need for John to leave the Army because of his inability to engage in further combat deployments (given the PTSD from his four previous combat deployments). During interim CAMS sessions, the clinician was able to gently persuade John to consider a medical separation from the Army, and together they engaged a VA provider who could see John after separation. They also explored various job options he could pursue as a civilian. Within a few weeks, with legal help from JAG, John obtained joint custody of his children and secured an arrangement for parental visitations. By session 9 of CAMS, John no longer had suicidal thoughts. While he was sad to leave the Army, John was excited about some job opportunities and the prospect of getting an associate degree with his VA benefits. John’s suicidal ideation had significantly resolved in fairly short order, and his symptoms of PTSD and anxiety were notably reduced. John actually felt hopeful about his future and ultimately became eager to leave the Army for a promising life outside the military.

In John’s case, we see all the elements of what Swift et al. found within their landmark meta-analysis of nine CAMS clinical trials. At the conclusion of CAMS, John began to realize a post-suicidal life—one with promise and potential for having successfully completed a therapeutic course of CAMS-guided care. While there were no doubt challenges ahead, John found his way out of a suicide crisis that put his life in peril. After his treatment, John saw that there could be life beyond being a Soldier,; a life with purpose and meaning—a life worth living.