According to the CDC, 12.2 million Americans seriously thought about suicide in 2020. 1.2 million actually made suicide attempts. With nearly 46,000 deaths per year, suicide remains a leading cause of death in the United States with rates of suicide steadily increasing over the past decade. Yet despite this health care emergency, mental health systems of care are largely underprepared to work effectively with suicidal individuals.

In response to these concerns, a recent policy initiative called “Zero Suicide” has advocated a systems-level response to the suicidal risk within health care and this policy initiative. And it’s working.

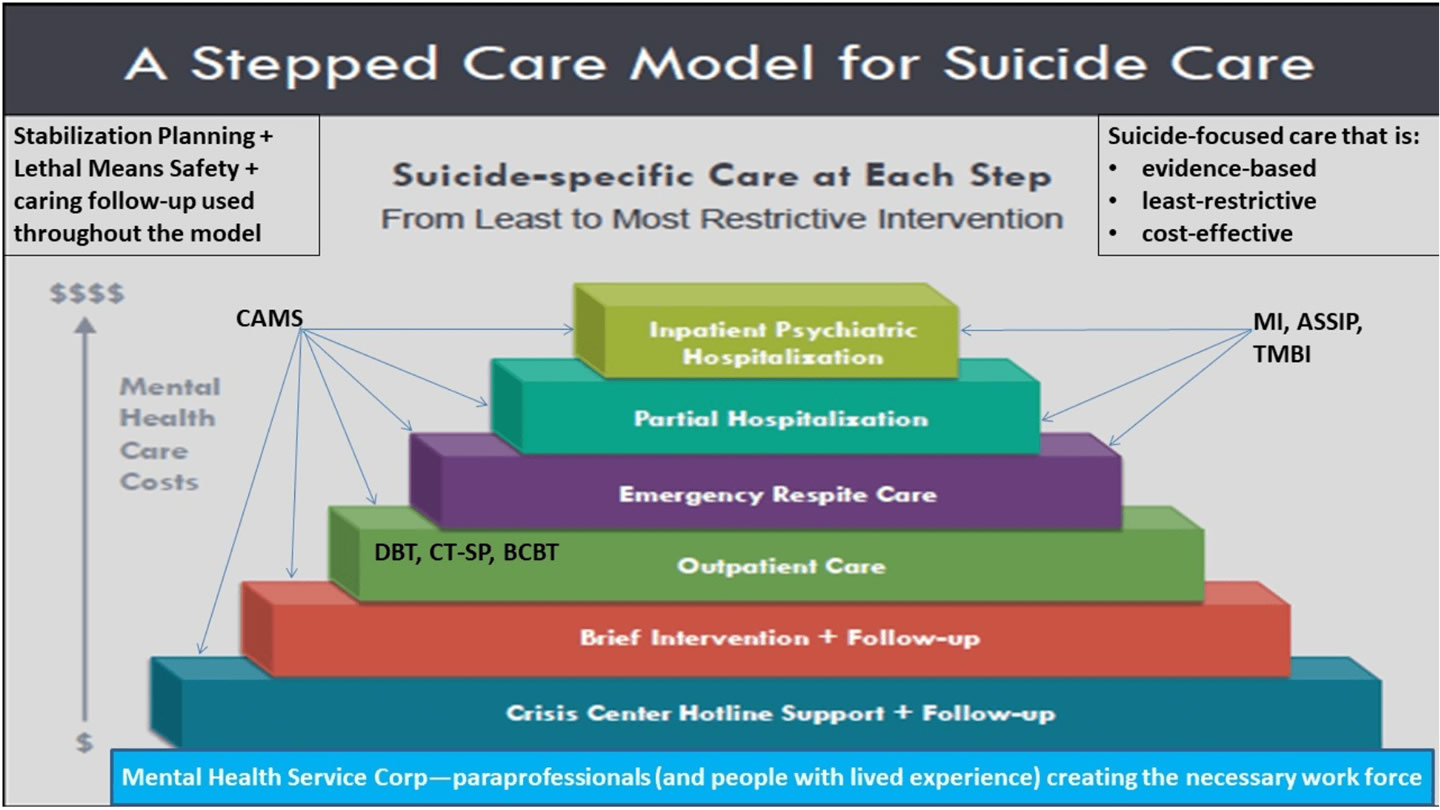

A “stepped care” approach has been developed and adapted to work within the Zero Suicide curriculum as a model for systems-level care that is suicide-specific, evidence-based, least-restrictive, and cost-effective. The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) is an example of one suicide-specific evidence-based clinical intervention that can be adapted and used across the full range of stepped care service settings.

This article describes several applications and uses of CAMS at all service levels and highlights CAMS-related innovations in the stepped care model. Psychological services are uniquely poised to make a major difference in clinical suicide prevention through a systems-level approach using evidence-based care such as CAMS. Here’s how stepped care can improve the effectiveness and efficiency of suicide care.

What is a Stepped Care Approach?

Stepped Care is a system of delivering and monitoring treatment so that the most effective and efficient treatment is delivered to patients first. Patients only “step up” to intensive/specialist services when it’s clinically required.

For example, a stepped care model for suicide care usually starts with suicide or crisis hotline support and follow-ups, like the 988 Suicide Helpline. This is followed by more involved and thus more costly and less easily scalable interventions like: additional follow-ups, emergency care, hospitalization, and finally specialist inpatient psychiatric care or hospitalization.

The goal of stepped care is to use evidence-based assessments, treatment plans, and patient tracking to allow the right people to deliver the right treatment in the right place at the right time to meet each patient’s needs.

Applications and Use of CAMS Across the Stepped Care Model

Suicide prevention and treatment is an immensely complicated and ever evolving field. However, thanks to evidence-based assessment and treatment frameworks, like The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) and tools like the Suicide Status Form (SSF) which is becoming a part of electronic health records across the country, clinicians can be more equipped to identify, treat, and ultimately prevent suicide.

CAMS has more than 30 years of evidence, five published randomized control trials, and two meta analyses one of which shows that CAMS is a “Well Supported” treatment by CDC criteria and is even proven to “reduce hopelessness and increase hope” in as few as six sessions. In fact CAMS is one of four evidence-based treatments that are referenced by the Joint Commission, Surgeon General and the CDC.

Click here to learn more about how we train physicians to use CAMS to treat and prevent suicide.

Crisis Hotline Support

Staffed by well-trained and compassionate professionals, suicide crisis lines are incredibly important tools in suicide care and prevention. They have the unique ability to provide vital crisis support to a range of suicidal individuals from all walks of life. But more importantly, crisis lines can effectively help suicidal individuals who may not be able to afford or even need costly clinical interventions.

CAMS can be a useful resource for call centers, since crisis center work typically focuses on assessing the immediate risk of suicide or suicidal thoughts through collaborative dialogue. The Suicide Status Form (SSF) is also a well-suited therapeutic assessment tool to efficiently stratify the level of risk during a crisis call, thanks to its easy to learn, structured, yet non-directive framework.

The SSF can also be used to track the ongoing risk of repeat callers, providing continuity of care when multiple crisis workers speak with the same caller over a period of time across shifts. Recent use of crisis text and chat lines present additional opportunities for using the SSF as a framework for collaborative suicide-specific engagement.

Brief Intervention

Emergency departments are often responsible for identifying, performing risk assessments, and referring suicidal individuals to specialist care, often in a high-volume, high stress environment. That’s a lot to ask from ED practitioners. That’s why we developed CAMS Brief Intervention (CAMS-BI™) to help meet this demand.

CAMS-BI is a single first session of CAMS using the SSF to learn about the patient’s suicide risk and the drivers of their suicidality, which leads to the development of a CAMS Stabilization Plan. CAMS-BI can be linked to non-demand caring follow-up contact in any way that’s agreeable to the patient including phone calls, text messages, e-mail, letters, etc. Emergency departments can also give out a Coping Care Package that includes various resources for patients to use after release.

Outpatient Settings

It’s essential for clinicians to attend to, assess, and treat suicidal risk in any mental health service setting. But the Suicide Status Form was originally developed for outpatient care, which means that CAMS is particularly well-suited for general outpatient mental health care services.

CAMS can help mitigate concerns regarding suicidal patients “falling through the cracks” by providing valuable structure and tracking support for both patients and clinicians. CAMS has even been adapted for use in several outpatient settings, including university counseling centers, community mental health centers, employee assistance programs, private practices, military, and Veterans Affairs behavioral health settings, and even successfully adapted to accommodate cultural considerations for use in countries around the world (Lithuania, China, Western Europe, and Australia).

Here is how CAMS is improving stepped suicide care in various clinical settings.

University Counseling Centers

CAMS has been successfully used in university counseling centers for years, and has proven to be especially adaptable to the unique culture of college life. One of the biggest strengths of CAMS on college campuses is how it integrates available resources in the university setting into the framework.

Empowering resident advisors, student-run organization, campus ministry, and health care services with the resources they need to help intervene with certain suicidal drivers and participate in the therapeutic process increases campus-wide awareness of suicidal risks while making the assessment and treatment stages of the process more efficient and effective for everyone involved.

Community Mental Health Centers

Clinicians working in Community Mental Health Centers often face unique challenges not limited to large case-loads, a chronic lack of resources, and an array of complex cases. CAMS can offer solutions to many of these challenges.

In a large-scale 5-year roll out of CAMS across the state of Oklahoma, CAMS was effectively adapted for CMHC patients with psychotic disorders and developmental delays. CAMS also increased hope and reduced suicidal ideation and overall symptom distress for outpatient CMHC patients, 40% of whom were homeless.

Independent Practice

Many clinicians in independent practice may feel particularly vulnerable and isolated when working with suicidal patients as they may not have access to various resources or a team of colleagues to help provide services and professional support. CAMS can provide clinicians with a clear procedural outline for assessing, treating, and tracking a suicidal patients’ progress, with tools like the SSF to increase their confidence and effectiveness at identifying and treating suicidal thoughts and ideations.

Military

Suicide remains a significant problem in the U.S. military, with many military Behavioral Health Clinics lacking a system for tracking ongoing suicidal ideation. As a consequence of this care gap many service members experience psychiatric hospitalization, which is not only inefficient, but often ineffective as suicide-specific treatment is typically limited.

Given the scope and scale of the problem, CAMS’ evidence-based, adaptable framework for assessing, tracking, and treating suicidal risk can provide an effective and scalable solution within military treatment facilities. It also addresses one of the biggest challenges for suicide care in the military — service members may not stay in one location long enough to complete a lengthy treatment protocol.

To help tackle this, CAMS aims to efficiently resolve suicidality in as few as six to eight sessions, and there’s a growing interest in the use of CAMS for military populations through telehealth.

Like standard CAMS, telehealth allows clinicians and behavioral health specialists to work together by jointly following the SSF as their clinical road map. Given the large number of service members who may not be able to access a treatment facility due to deployment, residing in remote areas, or physical disabilities, telehealth may provide a viable alternative to standard care. And many younger military members may also prefer a telehealth treatment option.

Veterans Affairs Outpatient Settings

Over many years CAMS has been extensively trained to providers across VA mental health treatment settings including VA medical centers and Community-Based Outpatient Clinics (CBOCs).

VA clinicians have a keen interest in the model and suicidal veterans anecdotally find the model helpful, but further clinical trial research is needed which is now being pursued by our research team.

Emergency Respite Care

As mentioned earlier, over the past several years, the state of Oklahoma has embraced the Zero Suicide policy model and has sought to systematically train CAMS to providers in their public mental health system. As part of their process improvement initiative, hundreds of outpatient providers and clinicians who work in brief intensive respite clinics have been trained to use CAMS in places where suicidal patients are stabilized over a 48-hr period and then discharged.

In the optimal care transition model, CAMS is initiated within crisis respite care to help stabilize the patient who is then discharged to a CAMS-trained provider who can continue the CAMS-guided care initiated in respite in an uninterrupted manner on an outpatient basis.

Partial Hospitalization

There has been some interest in using CAMS within partial hospitalization service settings. For example, there was some early clinical use of CAMS within a group format for severely mentally ill patients in a day treatment program within a VA Medical Center.

Partial programs offer intensive treatment in a more cost-effective and least-restrictive form of care. So it seems inevitable that CAMS will increasingly be used in such settings in the years ahead as a viable alternative to more expensive inpatient psychiatric care.

Inpatient Psychiatric Hospitalization

Within the current system of mental health care, individuals who are at imminent risk for suicide are often referred for inpatient care. And while the inpatient psychiatric setting may provide a safe and supportive environment for specific acute care services and stabilization, most of the interventions provided to suicidal patients are neither suicide-specific nor evidence-based.

In a report from the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC) and SAMHSA DJ Knesper noted:

“. . . the research base for inpatient hospitalization for suicide risk is surprisingly weak. This review could not identify a single randomized controlled trial about the effectiveness of hospitalization in reducing suicidal acts after discharge”.

Thankfully, this is changing as adaptations of the SSF and CAMS are being used to effectively assess and treat suicidal risk within inpatient settings. Most notably, the Mayo Clinic has used the SSF assessment to inform inpatient treatment and disposition discharge planning, and has further integrated the SSF into their routine assessment used with all patients at admission.

In terms of treatment, a Swiss team created an inpatient version of CAMS that was associated with dramatic decreases in overall symptom distress and suicidal risk in a sample of 45 suicidal inpatients over the course of 10 days of inpatient care.

Our team is currently exploring the use of an intensive inpatient version of CAMS, called CAMS Intensive Inpatient Care (CAMSIIC) which has been used in several inpatient treatment settings within the U.S. over a 3- to 6-day hospital stay. CAMS Brief Intervention involves conducting Session 1 of CAMS during a brief inpatient stay, necessitates the development of a stabilization plan, discussions of access to lethal means, and preliminary identification of issues in need of treatment (i.e., suicidal drivers) all of which should be quite relevant to the disposition of the patient upon discharge.

An adapted inpatient version of CAMS has also been used successfully at the Menninger Clinic in Houston, Texas. Referred to as CAMS-M, this adaptation offers CAMS twice per week with highly suicidal inpatients over a 50- to 60-day stay with clinicians focusing on intensively treating suicidal drivers while the nursing staff focuses on stabilization planning. The entire team then focuses on meaningful suicide-specific disposition and discharge planning.

In an initial open trial, a case series investigation of the effectiveness of CAMS within this longer-term inpatient psychiatric setting found statistically and clinically significant reductions in depression, hopelessness, suicidal ideation, and improvement in relation to suicidal drivers for 20 inpatients (Ellis, Green et al., 2012). A second study at the Menninger Clinic found significant changes in overall suicide ideation and suicide-related thoughts.

How CAMS Helps Diverse Populations

As a flexible clinical framework, CAMS has proven to be uniquely adaptable and modifiable to meet the needs of different patients, providers, and systems of care in the “real world” of psychological services. This adaptability has lead to CAMS being used to help diverse patient populations from suicidal inpatient teenagers at Seattle Children’s Hospital to suicide-specific group therapy within VA health care settings, and even the California state prison system and juvenile justice facilities in Georgia.

A systems approach to suicide prevention has clearly emerged as the best means for raising the overall standard of clinical care for suicidal patients with the promise of saving lives. Zero Suicide is a game-changing policy initiative that is gaining traction in the U.S. and abroad.

We have presented a stepped care model of suicide that is designed to treat suicidal risk in an evidence-based, least restrictive, and cost-effective manner. Moreover, we have shown the potential value of applying and using the CAMS evidence-based approach across the full range of psychological services—from paraprofessional interventions, to outpatient settings, to respite care, to partial care, and to inpatient psychiatric care.

CAMS may not work for every suicidal patient or setting, but it is highly adaptable and effective for a range of suicidal patients across systems of clinical care. Given that suicide is the fatality of mental health care, we urge members in our field to do all that we can to enhance our abilities to effectively assess and treat suicidal risk across the full range of organized health care settings to help save lives.

Contact us to learn more about CAMS training and a range of applications for CAMS and the SSF for clinicians and providers across the world.