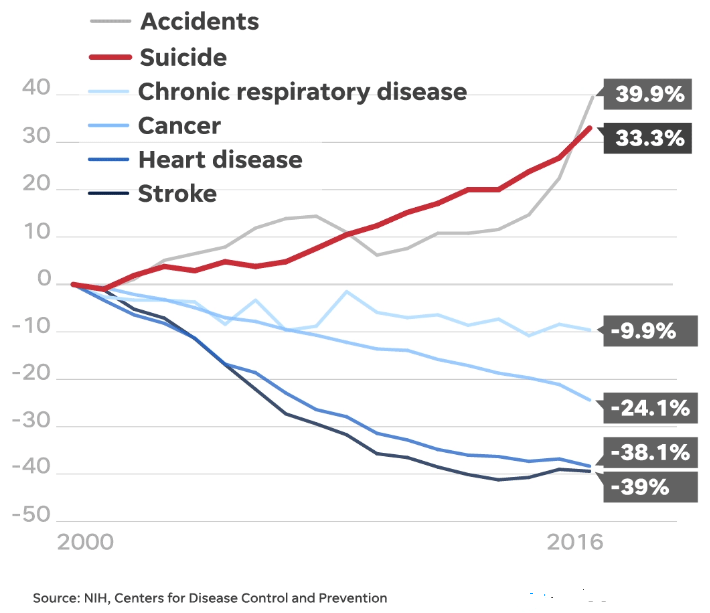

A recent AAS listserv exchange got me thinking about the abject fear that many mental health providers feel about working with suicidal patients. I have written on this topic many times and I routinely talk about this in my professional trainings. For people outside the field, this is a shocking thought—how could mental health professionals possibly fear suicidal patients? It is their job to care for any and all types, right? It is akin to a primary care provider being afraid of patients with heart disease (the #1 killer in the United States). Right?

Yet the fear is there and to be honest, it is not unreasonable; I myself have felt it. Being counterphobic, it is probably one of the biggest reasons I became an expert on suicide so I could feel some sense of mastery towards something that frankly makes me anxious and feel wary (not unlike becoming a technical rock climber in college to address my fear of heights). And yet I have managed to see and work with hundreds of suicidal people over 35 years of practice.

But in fairness to the fearful, let’s be candid: according to research, the vast majority of mental health providers receive little to no formal curricular training in the assessment and treatment of suicidal risk. Moreover, in our litigious society, the prospect of a family pursuing malpractice litigation is a very real and daunting threat. Many years ago, one of my students was involved in an interesting survey study wherein the majority of suicide loss survivors who lost their loved one (who was engaged in mental health treatment at the time of their suicide) perceived the death to be a result of clinical malpractice. Moreover, a significant subset of the sample reported actually contacted a plaintiff’s attorney to explore the prospect of malpractice litigation. It is therefore not a mystery as to why providers are scared and avoidant—they have not been trained to work with suicidal risk, and if they clinically “fail” there is the prospect of being sued for malpractice negligence.

The AAS listserv discussion initially focused on the notion that our legal system is the problem. In other words, considering the real and objective threat of litigation, there is a clear disincentive to working with challenging cases, particularly if they are suicidal. A psychiatrist on the listserv usefully noted that surgeons routinely turn away particularly challenging, low-probability-for-success procedures and no one really questions this aspect of surgical care (this psychiatrist was not defending the practice, just providing a point of reference).

This comment took me back some years ago when my oldest brother was facing an extremely high-risk heart valve procedure after a lifetime of battling cancer. In a professional and direct manner, his world-class surgeon said that my brother had perhaps a 15% chance of surviving an extraordinarily complex surgery. He said that it would be well within his practice parameters to decline such a high-risk case, noting it could “…hurt my batting average” (meaning that fatal surgical outcomes negatively impact his overall success rate). Please know that he did not say this cruelly or insensitively; he was just candidly stating the facts of the situation. In turn, we were not offended, and we understood clearly. But we nevertheless begged him to take the risk anyway and he eventually agreed. I can assure you that we signed a stack of legal documents designed to discourage litigation should there be a poor outcome. Sadly, my brother did not survive post-operatively. But here is the point: it never once occurred to us to sue him for malpractice. To the contrary, we were so grateful for the surgeon’s courage to take on my brother’ exceedingly difficult case. In fact, my sister-in-law visited the surgeon later that year to personally thank him for his heroic efforts to try and save her husband’s life.

I share this personal anecdote as a means of underscoring a larger need to realign how we think of high-risk clinical care. It is understandable that some healthcare providers may avoid such patients out of fear of failure and the pervasive blame-game that seems almost automatic when there is a poor outcome. But why can’t mental health professionals work more like my brother’s surgeon? Acknowledging to the patient and their family the full range of potential outcomes. Why can’t families sign a stack of forms that create some measure of legal top cover so providers feel like they can take the risk to care?

An obvious solution to all this was posted on the listserv by CAMS-care President, Andrew Evans. His post suggested that there might be much less blame and litigation if mental health providers would simply use one of the handful of suicide-focused clinical interventions proven to work by replicated randomized controlled trials (e.g., CAMS). Such interventions also embrace the importance of clinical documentation and professional consultation (both of which reflect good practice and help decrease liability).

To this end, I am reminded of a college student’s suicide, who had been previously seen in his university counseling center where he had received an extensive course of CAMS-guided care. Unfortunately, he dropped out of treatment and was non-responsive to a handful of efforts to get him to return to counseling center care. Following his suicide, his enraged father brought a high-priced plaintiff’s attorney to meet with his son’s therapist and the director of the counseling center. During the tense meeting the director presented the clinical record replete with CAMS Suicide Status Forms and detailed notation of the provider’s extensive efforts to get the patient to return to care. The lawyer closed the record, looked at the father and said: “…we have no case…there is simply no negligence here to go after.” The furious father hired two more attorneys who both came to the exact same conclusion.

My friend and colleague Susan Stefan (a premier mental health legal scholar) and I have occasionally talked about the prospect of creating legal documents—a waiver of sorts—for mental health providers to use with patients and their families that might help assure some degree of protection for clinically engaging high-risk suicidal patients. Such a waver would not necessarily make a provider “bullet proof” from malpractice litigation, because there must be consequences for reckless and negligent clinical care. But similar to the documents that we signed with my brother’s surgeon, short of gross incompetence or clinical negligence, the family would not frivolously sue because of a fatal outcome. More to the point, such a waver might help decrease mental health providers’ abject fears of seeing suicidal patients while increasing their willingness to take the risk to care – and potentially save more patient lives from suicide.

Related Articles:

Suicide Malpractice Statistics

Mental Health Malpractice: Greatest Fear of Care Providers

Mental Health Providers: Top 5 Ways to Limit Malpractice Exposure