While the American public was preparing for the Holiday season, on December 17, 2019 Rep. Bonnie Watson (D-NJ) introduced a bill to U.S. House of Representatives.1 H.R. 5469, or more commonly known as the “Pursing Equity in Mental Health Act of 2019”, proposes to allocate funding to organizations to address mental health problems among youth of color. This bill specifically pertains to addressing the epidemic of suicide among Black adolescents. In the early months of 2019, an emergency taskforce was formed by the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), which included research findings that were based on the collective work of Black professionals within numerous fields of expertise.

The report states that suicide is the second leading cause of death among Black adolescents between the ages of 10-19.2 The report further states that Black youth disproportionately die by suicide at higher rates than other races/ethnicities. In the last decade, suicide rates for Black adolescents have increased by 73%.3 Contrary to the trends we observe with Black adolescents, current research finds that the suicide rates among Black adults are relatively low in comparison to White counterparts.4

Focus of the Pursuing Equity in Mental Health Act

The Pursuing Equity in Mental Health Act of 2019 aims to:

- Increase research on the risk factors, preventative factors, and methodology of suicide within Black youth, and

- Support organizations focused on providing holistic, mental health treatment.

The current literature of research tackling the suicidology of Black adolescents is minimal. An explanation for this conundrum maybe explained by implicit bias within research. The congressional report mentions a study that found that Black researchers are denied funding 10x the rate of White researchers.11 There is a necessity for research and treatment concentrated on the alarming trend of suicide among Black youth.

Based on my research with CAMS (Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality), my research interest aligns with examining suicidal behavior within marginalized individuals (i.e., racial/ethnic, gender, and sexual minorities). In this article, I provide suggestions for the allocation of future research, treatment, and interventions supported by the proposed bill.

But first, why do we observe this alarming trend among Black youth? There are a few risk factors that influence suicide and suicidal behavior among this demographic.

Risk Factors

Trauma & Social Media

The image of a dead or injured Black body flashes across the screen of a personal computer or smartphone.

While scrolling through any of multiple, popular social media sites, a teenager may view dozens of these images. In the age of technology, sharing information across platforms is instant, and unfiltered. Whether accurate or appropriate, the information is available.

This increased exposure to graphic images shared among social media has been shown to increase depression and suicide among adolescents.5,6 In addition, other psycho-social stressors such as SES, academic opportunities, and systematic marginalization may contribute to suicidal behaviors among black adolescents. 7

LGBTQ+ Identity

Individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ experience higher rates of suicidal behavior than other groups. 8 Association of this risk factor is often linked to bullying, lack of social acceptance, and heightened occurrence of homelessness. These trends are evident across race/ethnicity and age.

Implicit Bias and Stigma

There is a history of mistrust and bias that permeates the therapeutic relationship between the African American community and a “white” mental health field, stemming from the origins of racist pseudo-science and unethical experimentation.9 This is among several reasons Black people are often reluctant to seek mental health support. Another factor that may contribute to an increase in suicidal behavior among Black youth is perceived social stigma. Black adolescents with mental illness experience stigmatization from family, communities, and the larger society.10

Future Research and Treatment

It is appropriate for allocations of funding to go towards organizations/individuals who are already working with suicidal Black youth. These individuals would already have established rapport within the community and possess advance knowledge on implementing research and providing support. By focusing attention on the existing expertise within this area, we help to lessen the “learning curve” and improve training towards other professionals who have Black clientele.

There are a multitude of established literature on the effectiveness of treatments for suicidal individuals. When working with marginalized groups, it is important to incorporate what works. Why fix what is not broken? Just adapt.

Research has shown that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectic Behavioral Therapy (DBT) are effective in treating suicidal behaviors.12,13 Furthermore, research also highlights the effectiveness of CAMS as a therapeutic framework.14 What makes these treatments work? The use of client-focused therapy and incorporation of holistic methods (e.g., collaborative approach, community engagement, cultural inclusion, etc.) are the foundations that stabilize these interventions.

A CAMS Hypothetical Randomized Control Trial (RCT)

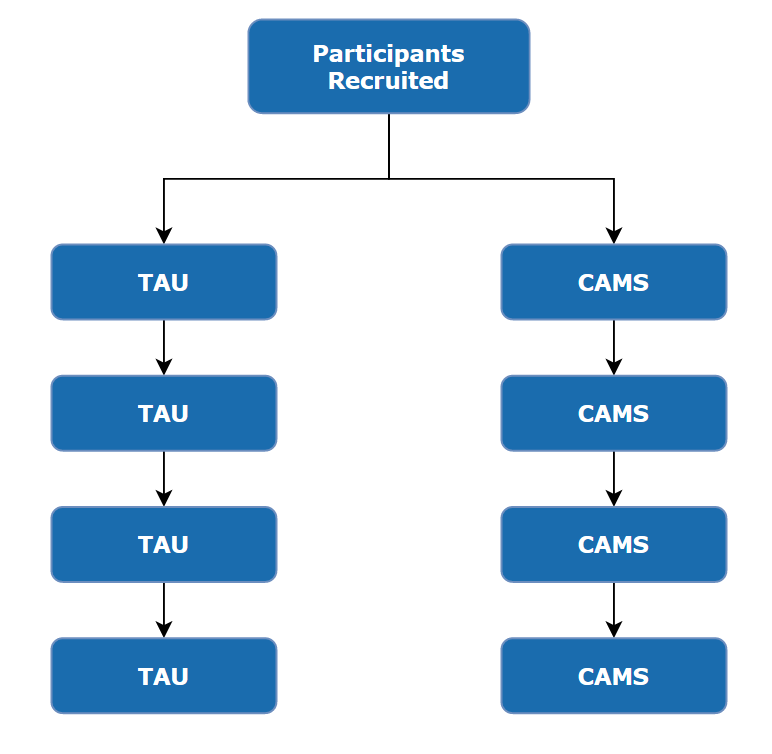

The efficacy of CAMS was initially measured using RCTs. Suicidal clients (whether recruited through outpatient centers, universities, etc.) were split into a treatment as usual (TAU) group in comparison to the CAMS administered group.15 The Suicide Status Form (SSF) was used as a guide to administer CAMS between the clinician and client. The TAU and CAMS groups were compared after the initial and consecutive sessions.

A similar design could be applied when using an RCT to compare TAU with CAMS in a sample of Black adolescents with a history of suicidal behavior. These participants possibly could be recruited from outpatient centers, counseling centers on college campuses, middle school and high school programs, and through other organizations. Of course, these individuals must meet the requirements of race/ethnicity and a history of suicidal behavior and/or mental health.

Based on previous CAMS RCT research, a hypothetical study is outlined in the flowchart below:

Figure. A flowchart depicting an RCT examining the efficacy of CAMS treatment within a sample of suicidal Black adolescents.

Conclusion

If the Pursuing Equity in Mental Health Act of 2019 is passed into legislation, it will be a milestone for research and treatment of suicidology within Black adolescents. The rising trend of suicide among this group rings warning signs, which call to action experts who provide an interdisciplinary lens to research and treatment.

More extensive and intense research into the risk and preventative factors of suicide among Black youth may begin to tackle a stressor of systematic marginalization. Implementing more efficient mental health treatment specifically designed for this demographic may provide holistic and cost-effective interventions.

As I continue my work as a Black researcher and clinician, I am discovering that integrating a client-focused, community-centered, and culturally inclusive approach into therapy/research is the difference between life and death for our clients.

- References World Health Organization. Suicide Rates (Per 100,000 Population); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Emergency Taskforce on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health. (2019). Ring the Alarm: The Crisis of Black Youth Suicide in America. Retrieved from https://watsoncoleman.house.gov/uploadedfiles/full_taskforce_report.pdf

- Runcie, A. (2019, December 17). Proposed legislation attempts to address rising suicide rates among black children. CBS News. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/proposed-legislation-attempts-to-address-rising-suicide-rates-among-black-children-2019-12-17/

- Leong, F. T. L., Nagayama Hall, G. C., McLoyd, V. C., & Trimble, J. E. (Eds.). (2014). APA handbook of multicultural psychology (Vols 1 & 2). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Twenge, J.M., Joiner, T.E., Rogers, M.L., & Martin, G.N. (2017). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among u.s. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychology Science, 6, 3-17.

- Feuer, V., & Havens, J. (2017). Teen suicide: Fanning the flames of a public health crisis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 723-724.

- Hope, E.C., Hoggard, L.S., & Thomas, A. (2015). Emerging into adulthood in the face of racial discrimination: Physiological, psychological, and sociopolitical consequences for african american youth. Transitional Issues in Psychological Science, 1, 342-351.

- Pritchard, E.D. (2013). For colored kids who committed suicide, our outrage isn’t enough: Queer youth of color, bullying, and the discursive limits of identity and safety. Harvard Educational Review, 83, 320-345.

- Washington, H.A. (2006). Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on black americans from colonial times to the present. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- Rose, T., Joe, S., & Lindsey, M. (2011). Perceived stigma and depression among black adolescents in outpatient treatment. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 161-166.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Emergency Taskforce on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health. (2019). Ring the Alarm: The Crisis of Black Youth Suicide in America. Retrieved from https://watsoncoleman.house.gov/uploadedfiles/full_taskforce_report.pdf

- Stanley, B., Brown, G., Brent, D.A., Wells, K., Poling, K., Curry, J., …Hughes, J. (2009). Cognitive-Behavioral therapy for suicide (cbt-sp): Treatment model, feasibility, and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 1005-1013.

- Ougrin, D., Tranah, T., Stahl, D., Moran, P., & Rosenbaum, A. (2014). Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 97-107.

- Jobes, D.A., Moore, M.M., & O’Connor, S.S. (2007). Working with suicidal clients using the collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (cams). Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 29, 283-300.

- Jobes, D.A., Au, J.S., & Siegelman, A. (2015). Psychological approaches to suicide treatment and prevention. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry, 2, 363-370.

For more information

To learn more about effective methods for working with suicidal minorities, read “5 Effective Approaches When Working with Minority Clients” by Tanisha Esperanza Jarvis, M.A.

Learn More About CAMS-care’s Approach to Suicide-Prevention Training

Discover a comprehensive suite of suicide assessment, prevention and treatment resources at CAMS-care. Our expert suicide prevention training, professional consulting, and valuable resources are designed to empower those seeking to combat suicidality & suicidal ideation.

Training offers include CAMS Trained™as well as CAMS Certified™ designations. To learn more about the CAMS Framework® of suicide prevention, contact us today.